The Prison Industrial Complex and Modern Day Slavery

Photo Source: https://georgetownvoice.com/2020/10/24/divest-from-the-prison-industrial-complex/

November 20, 2021

Slavery never left our country; it simply took a different form.

The prison industrial complex was born the very day the 13th amendment was passed; the very second the phrase “except as a punishment for crime” was etched into our Bill of Rights.

The Background

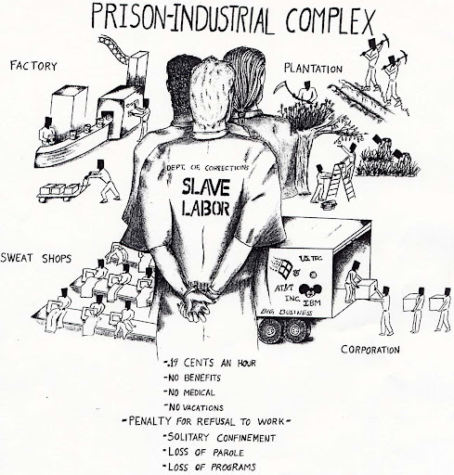

The prison industrial complex refers to the profit-driven relationship between the government and big business, where imprisonment is seen as the solution to economic and sociopolitical problems and a means to obtain free labor.

The official term may be relatively new, but the prison industry itself didn’t form overnight. The intent to use prison labor to rake in large profits emerged immediately after the fall of slavery.

With the expulsion of slave labor and the collapse of the Southern market, Southern legislatures knew they had to do something fast to rebuild their economy. With a newly freed population of 4 million black people, and no effort to unlearn any of the violent racist behavior that runs rampant in America, the government did not have to think long nor hard about what to do to counteract this economic collapse.

Homelessness was criminalized, unemployment was illegal, loitering was considered prison-worthy behavior. Legislation against ‘mischief’ and ‘insulting gestures’ were put into practice.

Anybody convicted of a crime could be leased out by the state to private companies who would then exploit them for labor for measly wages- if any at all. Suddenly, the South had its labor force back, and its black population under control once again.

These laws, of course, were only enforced against African Americans, as thousands of black people were arrested and sold as forced laborers throughout the South.

Death rates were incredibly high, because, unlike slave owners, who had to make sure their slaves didn’t die, private contractors had little to no interest in the health of their laborers since they had a ready supply waiting for them back at the jail.

Convict leasing wasn’t officially outlawed until 1945, and, up until the end of Nixon’s presidency, the general public saw prisons as unfit for prisoners. Some of the most well-respected criminologists were predicting that the prison system would soon fade away.

That was the mid-1970s, just years before the Reagan administration, before the era of mass incarceration, before the War on Drugs and the War on Crime changed from metaphorical to literal, and before the government started a war on its black citizens.

The War on Drugs was the government deciding to deal with drug addictions and dependency as a crime issue rather than the health issue it is; the War on Crime was a code word for President Nixon fighting against the black political movements of the day.

The Watergate co-conspirator John Ehrlichman even admitted in 1994 that the War on Drugs was a specific attack on black people:

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Hundreds of thousands of black people were sent to jail for possessing weed and other low-level offenses. Crack cocaine, more commonly in the inner cities, had a far harsher punishment than powder cocaine, which was more common in the suburbs (same prison time for 1 ounce of crack for 100 ounces of powder).

Then came mandatory sentencing and the 3 strikes laws, which completely removed a judge’s discretion and any consideration of the circumstances surrounding a crime.

Mandatory sentencing requires that offenders serve a predefined term for certain crimes, commonly serious and violent offenses. The 3 strikes law is a criminal sentencing structure in which significantly harsher punishments are imposed on repeated offenders. Three-strikes laws generally mandate a life sentence for the third violation.

Families, specifically black families, were torn apart by these racially targeted laws.

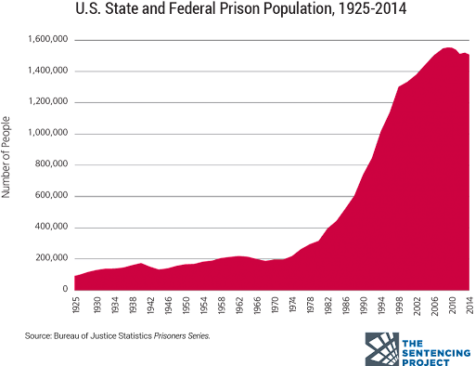

The criminalization of living as a black person in America is the backbone of mass incarceration and what keeps prisons alive today. The prison population boomed, and with it came the revival of convict leasing, just under a different name.

Prison labor is convict leasing with a poorly done facelift.

As a pillar of private prisons, this forced labor is a major profit for prison owners, as they can use their inmates as unpaid laborers in order to cut down on production costs and raise take-home earnings for themselves.

The New Jim Crow, Mass Incarceration, and The War on Drugs

Like slavery, Jim Crow evolved to fit a new era as well.

Once incarcerated, returning citizens are no longer able to vote, exercise their civil rights, or serve on a jury, and can be legally discriminated against in employment, housing, and public benefits, like food stamps and health care.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

This isn’t an accident. Not at all. As stated before, the collapse of slavery left the Southern economy in a wreck, leading governments to create numerous laws that would only affect, and be enforced against, black people. This resulted in mass amounts of former slaves being arrested and sold into convict leasing, sold into the renamed version of slavery.

Today, once released from prison, returning citizens are then subject to the newly re-legal Jim Crow discrimination; locked out of the economy and mainstream society permanently.

Mass incarceration had a huge hand in just how many black people are locked out of society- and Reagan’s War on Drugs had a huge hand in creating the formation of the modern prison industrial complex.

At the time Reagan declared a war on drugs, less than 2% of the American public viewed drugs as an issue worthy of national attention, making it very obvious that this declaration had little to do with concern about drugs and more to do with concern about race.

This can be seen in how the Reagan administration funded government programs.

Between 1980 and 1989, FBI anti-drug funding increased from $8 million to $95 million. Department of Defense anti-drug funds increased from $33 million to $1.042 billion. The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) anti-drug spending grew from $86 million to $1.026 billion, and FBI anti-drug funding grew from $38 million to $181 million.

However, during the same period, the funding for agencies responsible for drug treatment, prevention, and education was dramatically reduced. The budget of the National Institute on Drug Abuse was reduced from $274 million to $57 million, and anti-drug funds allocated to the Department of Education were cut from $14 million to $3 million.

No one should try to minimize the harm caused by crack cocaine and the related violence, but we had a choice in how to respond. Numerous paths were available to the government in the midst of the crack crisis, yet we chose war.

The DEA trains police to perform unreasonable and discriminatory stops and searches. Officers learn a variety of things during this training, but most notably how to use a minor traffic violation as leverage into a search for drugs, how to gain consent from a reluctant driver, and how to use drug-sniffing dogs to obtain probable cause (police discretion is an entirely different subject that deserves its own article, for more information, see here.)

The police are trained to create a reason to put people in jail, trained to create free laborers, and trained to take away civil rights.

In 2019, 13,459 stops by the NYPD were recorded. Of those almost 14,000 stops, 7,981 were black (59%), while only 1,215 were white (9%).

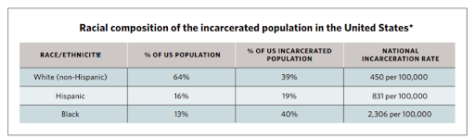

White men have a 1 in 17 chance of being jailed at some point in their lifetime. Black men have 1 in 3. Black men are admitted to state prison on drug charges at a rate that is more than 13 times higher than white men, even though drug use between black and white men is relatively the same. Black men make up 6.5% of the population, yet account for 40.2% of the prison population.

It was never about the drugs, it was about putting people in jail. It was about putting black bodies in jail.

That’s 1 in 3 black men who will be denied the right to vote and their civil rights. That’s 1 in 3 black men who will be legally discriminated against in employment, in housing, in public benefits, in all the ways that were once legal during Jim Crow, in all the ways that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 supposedly outlawed.

In the same way slavery wasn’t abolished, Jim Crow was never outlawed. Both institutions simply adapted to the new time period.

Capitalism, Capitalism, Capitalism

Everything, and I mean everything, ties back to capitalism.

The association of crime with black people is more than just a racist delusion, it’s also an idea embedded in capitalism’s need for a cheap and exploitable labor force.

The use of racism to create this cheap and exploitable labor force goes back to the 1670s when Nathanial Bacon led a rebellion composed of both white indentured servants and black slaves.

After the rebellion was squashed, the Southern white elites realized something needed to be done to prevent this type of unionizing from happening again; so, they created tension between the two groups. They told the white indentured servants that the black slaves were after their jobs, and that they, as white people, were superior to the slaves solely because of their skin color. Following the white elites’ plan exactly, white indentured servants were eager to have a group trapped lower in society than they were, thus creating two separate groups ready to be exploited for their labor.

We may have abolished slavery, but we still live in a racist and capitalist country, a racist and capitalist country that always needs cheap, exploitable labor, and that always, always, looks for more ways to make money.

The United States government has contracts with corporations to manage correctional facilities, making them private prisons. Two corporations, CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America) and GEO Group, account for over half of our private prison contracts.

Both GEO Group and CoreCivic make much of their profits from ICE detention centers, and, like all other privatized prisons, get revenue by charging governments to house people in their jails. A private prison can offer its services to the government and charge $150 per day per incarcerated individual.

These contracts prove to be extremely profitable, as GEO Group and CoreCivic earned 4 billion dollars in profit combined at the end of the fiscal year 2017.

These corporations are invested in maintaining high incarceration rates because it’s profitable to them. There are corporations in our government trying to make sure our police force throws enough people in jail so they can still make large profits.

Many corporations that provide prisons with services grossly overcharge for what they give. Companies such as Securus and Keefe price a 15-minute phone call at $25, and take $6 from people trying to deposit a mere $20.

Because these corporations are relatively unregulated, they’re also able to participate in the modern-day slavery that is prison labor. Many companies heavily rely on a constant number of incarcerated individuals to comprise their labor force.

Returning citizen Robert Rose III recalled what it was like to have corporations running the prison industry:

“I spent more than 24 years in prison. I saw how corporations exploited people in the closed prison market—from telephone calls to commissary to labor. We were a captive audience without a say in what were often monopoly contracts. They could gouge us or offer terrible service without ever worrying about losing business.”

In a 2020 report done by Worth Rises, over 4,100 corporations were exposed for profiting from mass incarceration and prison labor. It’s important to note that these are just the companies who were transparent about how they get their labor.

For all 4,100 companies, click here.

Allstate, AT&T, Bank of America, Barnes & Noble, and Coca-Cola are just 5 of the thousands of corporations that use and profit off of modern slavery.

Prison labor is inexpensive, mostly free, which motivates more companies to use it to cut down on their labor costs to bring in a greater profit.

There is no regulation when it comes to this type of labor, it’s completely legal, per the 13th Amendment. Therefore, meaning that they can pay their laborers however much, or little, they want.

The average low minimum wage pay of these forced workers in non-industry jobs is $0.14, with the average high being $0.63. Industry jobs aren’t much better, with an average low minimum wage of $0.33 and an average high of $1.41.

Our home state Massachusetts pays an average low of $0.14 and an average high of $1 for non-industry jobs; we don’t offer any industry jobs. Remember, these are just the averages, meaning that yes, some prisons pay higher, but some, most, pay lower. Some states, such as Arkansas and Georgia, don’t pay their laborers anything. They use the labor of people in prison completely free (for more state averages, see here.)

Prisons are prime sites for exploitation and cost-cutting.

Long-time Civil Rights Activist and author Angela Davis put it this way:

“For private business, prison labor is like a pot of gold. No strikes. No union organizing. No health benefits, unemployment, insurance, or workers’ compensation to pay. No language barriers, as in foreign countries.”

Extremely cheap labor is a large motivating factor to fill up prisons with more people, with more laborers, to bring in more profit.

Kevin Rashid Johnson, a social activist and currently incarcerated, wrote an article about the horrors he has personally seen in jail due to the capitalistic need to cut corners and lower expenses in order to rake in a larger profit.

He states:

“Though I’ve always refused to engage in this modern slavery myself, I’ve witnessed plenty of examples of it. The most extreme were in Texas and Florida, where prisoners are forced to work in the field for free, entirely unremunerated. They are cajoled into chain gangs and taken out to the fields where they are made to grow all the food that inmates eat. They are given primitive hand-held tools like wooden sticks and hoes and forced to till the soil, plant, and harvest cotton. They are watched over all day by guards on horseback carrying shotguns. Prisoners who do not agree to such abject slavery are put in solitary confinement. I know from personal experience. Racial animus is always present.”

Johnson ends his article by noting that he will face reprisals for writing his piece, but he holds no fear for it.

“I am far past the point where threats concern me. In the past three decades, I have endured every level of abuse they have to offer: I have been starved, beaten, dehydrated, put in freezing cold cells, attacked with attack dogs, rendered unconscious, chained to a wall for weeks. There’s nothing left to fear.”

On one end of the capitalism spectrum are the corporations, on the other are the police. The police, who were given huge cash grants by the Reagan administration to make drug law enforcement a top priority. The police, who were given military intelligence and war weapons to make the rhetorical war on drugs a literal one. And, finally, the police, who were given permission to keep, for their own use, the vast majority of cash and assets seized.

This permission, given to the police by, again, the Reagan administration, gave law enforcement agencies an enormous stake in the very existence of the drug war, not in the success of ending it. (Once again, the police force in itself deserve a whole separate article, but for more information see here.)

Once you’ve been convicted of a crime you are, in essence, a slave to the state. You lose your civil liberties and civil rights all so the government and corporations can make a profit.

Prison Contracts: Profits, Politics, and Cheap Labor

As touched upon briefly before, private prison corporations are heavily involved in our politics

CoreCivic and Geo Group, in particular, have spent millions of dollars on lobbying and campaign contributions, always looking for opportunities to market their interests and to gain the favor of politicians.

They send lobbyists to Congress to sway politicians into maintaining, as well as strengthening, laws that sustain our high incarceration rate, such as minimum occupancy clauses.

Around ¾ of private prison contracts include, in one way or another, a minimum occupancy clause. Also known as a ‘bed guarantee,’ these clauses state that the prison in question has to maintain a certain prison population, filling at least 90% of the beds at all times. If a state fails to do so, it must pay a fine to the private company running the prison.

Governments are incentivized to arrest more people to avoid financial penalization from corporations.

Let that sink in.

Capitalism runs so deeply in America that the literal government bends to the will of big business.

In order to make money, privatized prisons are set up to need a lot of prisoners, this is where the political lobbying comes in. Minimum occupancy clauses resulted in over two million people being imprisoned in 2014 alone. This is because the state governments needed to meet lockup quotas in order to avoid paying the corporations that own the prisons. The vast majority of people in jail aren’t there for violent crimes; most people are there for drug charges with no prior record.

In the same year, China had around 500,000 fewer people living in prison even though they have five times as many citizens as the United States.

Another major political scheme behind the prison industrial complex is the use of mandatory minimum sentencing.

As mentioned in the first subheading, mandatory sentencing requires that offenders serve a predefined term in prison. This is the main reason for skyrocketing incarceration rates seen during the 1990s into the 2000s. As a result of the exploding prison population, a new prison was built every 10 days from 1990 to 2005.

As a country, we have the highest incarceration rate in the world. We incarcerate 639 people per 100,000, 13% higher than the next closest country (El Salvador). Even though we represent under 5% of the global population, we hold around 20% of the world prison population, making 1 out of every 4 people in prison being locked up in America.

Prison construction, and the accompanying drive to fill these new structures with laboring bodies, have been driven by ideologies of racism and the pursuit of profit.

There is a direct correlation between the rate of incarceration and profit.

From 1980 to 1994, the number of people incarcerated rose from roughly 300,000 to 800,000, and in conjunction, private prisons witnessed an almost billion-dollar rise in earnings, as profits rose from $392 million to $1.31 billion.

The prison industrial complex and modern-day slavery have become indispensable components of the American economic system. The connection between police departments, court systems, probation offices, transportation companies, food service providers, etc, is difficult to ignore, especially when all of them ultimately benefit from upholding mass incarceration in such a significant way.

One of the scariest political factors of it all is the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC for short.

ALEC is a conservative organization made up of state legislators and private sector representatives who draft and share model legislation for distribution among state governments.

Some examples of their work include creating the template for the Prison Industries Act, the 3 Strikes Law, mandatory minimums, and the “truth-in-sentencing” laws.

Truth-in-sentencing laws are the policies and legislation that aim to abolish or curb parole so that convicts serve the entire period to which they have been sentenced.

Due to ALEC’s mandatory minimum sentencing laws, 97% of people in prison have plea bargains. People are pleading guilty to crimes they didn’t commit just because the thought of going to jail for what the mandatory minimums are is so excruciating.

People would rather admit to a crime they didn’t commit rather than endure 10 years of working on a chain gang for $0.14 an hour, if any pay at all

Sickeningly enough, the American Bail Coalition also belongs to ALEC. To recap, not only does ALEC create the laws that put millions behind bars, but they also hold the key to releasing them too. People are in jail for no other reason than being too poor to get out.

As the Netflix movie 13th put it, we have a criminal justice system that treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent.

This is exactly how they want it: keeping bodies in prison and saving millions off their labor.

Conclusion

We have to understand that we are the products of our ancestors’ choices in order to escape from them. Our ancestors chose war and capitalism over the well-being of their citizens.

Unfortunately, I don’t have an answer to this problem, at least not an immediate one. The prison industrial complex is a vast and complicated system that, most likely, won’t go away as long as capitalism is still thriving in America. However, that doesn’t mean that we as people can’t do our own part on the road to dismantling modern-day slavery and the stigma that follows formerly incarcerated individuals.

The first, and easiest, step is to be kinder toward the formerly incarcerated and people in prison.

Change your vocabulary when referring to them in conversation. Instead of referring to someone as a felon, use returning citizen or formerly incarcerated. Instead of using inmate, say person in prison.

For some, this may seem “inconvenient” because it’s cumbersome to say, but, to be quite honest, who cares? It’s important to value the dignity of those who have been caged, to emphasize their humanity in a time of criminalization and mass incarceration.

More than 70 million Americans, over 20% of the country’s population (overwhelmingly poor and people of color) now have a criminal record, and can be legally discriminated against for the rest of their lives. This is not a new era of racial awareness, not when the very systems that we use to differentiate this era from the last are still alive, thriving, and legal.

I encourage everyone who reads this article to research further into any of the topics discussed. I can’t even begin to imagine how long this article would be if I gave every single aspect or piece of history of the prison industrial complex the rightful attention it deserves. The Reagan presidency itself needs a whole separate article to cover the disaster it was.

The Prison Industrial Complex is perhaps the greatest evil of the 21st century. With corporation and government interests intersecting to contribute to the most disgusting human rights violation of this century.

In prison, people are seen as nothing more than working bodies. Outside of prison, formerly incarcerated individuals are barred from their right to live. It’s sickening.

This is an expansive problem, fluid, and ever-growing; the only way we can hope to make change is by starting small.

Start with how you refer to those who are or have been incarcerated. Start with taking note of how society treats those who have been imprisoned. Start with noticing which companies profit off of the suffering of people in prison.

Start small; making small changes is always the first step down the long road of progress

Below I’ve included a list of books and movies that I urge everyone to read and watch to learn more about what is, and what isn’t, addressed in this article.

Movies:

13th

The Farm: Life Inside Angola Prison

The House That I Live In

Louis Theroux: Behind Bars

Serving Life

Books:

The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander

Are Prisons Absolute? by Angela Y. Davis

The Prison Industrial Complex by Angela Y. Davis

Policing the Black Man by Angela J. Davis

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime by Elizabeth Hinton

From Deportation to Prison by Patrisia Macias-Rojas

Invisible Punishment: The Collateral Consequences of Mass Imprisonment by Marc Mauer