American Terrorism

Source: Carlos Latuff

April 7, 2022

American Interests Unmasked

Every single time the United States has been involved in a regime change, be it through a coup, invasion, military occupation, etc., it has always been for one of two things: anti-communism or protecting American businesses. Every. Single. Time.

Each time we overthrew a left-leaning leader, or blocked one from ever gaining power, it was always cloaked in a false narrative of national security threats.

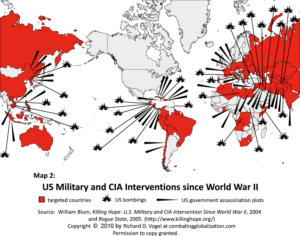

Between 1947 and 1989 alone, America attempted to change another nation’s government 72 times. There were many different ways our government went about this, outright coups, covert operations, military support for rebel groups. Still, the most successful was influencing foreign elections with secret funding, advertising, and propaganda. The U.S.-backed candidate won office 75% of the time.

If there’s one thing you can count on America to do, it’s to choose to maintain influence and power over spreading democracy. Every time we were posed to overthrow a government, the same question was asked: do we allow a new democracy to flourish, or do we make things easier for American businesses? It was always an easy choice.

You’ll find it a common theme amongst all these interventions that the United States never cared about people, just about profits.

Although America has intervened in a multitude of countries, this article will focus specifically on American involvement in parts of the Middle East, parts of Latin America, and a handful of other countries.

I tried to cover every single government we’ve ever overthrown, but this led me to an over 50-page document that had no end in sight (that should give you a pretty clear picture of American foreign policy and what we actually care about.) It’s never been fueled by any kind of moral commitment to helping impoverished nations; it’s always been to make the world safer for American corporations and to prevent the rise of any successful example of an alternative to capitalism.

Latin America:

Puerto Rico, 1898

To America, Puerto Rico was simply a strategic move. It was never anything other than a stepping stone to the world stage.

Our government even admits that Puerto Rico’s value was solely “centered in economic and military interests. The island’s value to US policymakers was as an outlet for excess manufactured goods, as well as a key naval station in the Caribbean.”

Puerto Rico marked the start of a long line of military interventions purely motivated by profits and no consideration for the people who lived there.

Puerto Rico was given autonomy from Spain in 1897. America took away that autonomy in 1898 when they invaded Puerto Rico and seized control of the country as a strategy during the Spanish-American War. Puerto Rico became a war prize. America installed a military government in October. When the Treaty of Paris was signed in December, Puerto Rico (along with Guam and the Philippines) was handed over to the United States.

This new military government dedicated itself to attacking anyone opposed to it and devoted much of its time to suppressing any media offering criticism of the invasion and occupation. Journalists were systematically targeted and arrested. Anybody speaking on the behavior of the occupying troops was in danger. Any activity that might lead to destabilization or threatened economic interests was repressed.

American interests, of course, were protected and prioritized, while class conflict, violence, and the loss of fundamental civil rights raged on.

Then, in May of 1900, Congress ended the military regime with the passage of the Foraker Act, which began the process of recolonization through the facade of a civilian-run government. While Puerto Rico now had the feel of their own government, it was really only the President of America who could appoint governors and members of the upper house of its legislation, leaving only the lower house open to public election.

The Foraker Act allowed for the American government and its commercial interests to stay indefinitely in Puerto Rico to further expand our greedy hands into the rest of the Caribbean.

With the island’s economy held captive by the American government, Puerto Rico was thrown into a long-term dependent relationship with the United States. American corporations established the prices for items as essential as gas and bread. Salary levels were set as well. Working conditions were nothing short of shameful.

With the help of the president of the Nationalist Party, Pedro Albizu Campos, a 1934 strike was organized to protest the deplorable treatment of sugarcane workers. The Nationalist party was characterized by radical anti-imperialism and a strong affirmation of a separate Puerto Rican identity. The Party revived Puerto Rico’s independence movement. They spread their message through mass media and began a war with the colonial regime they lived under. This regime then persecuted, imprisoned, and assassinated the Party’s leaders for the next 20 years.

In 1948, a Gag Law was signed into practice to suppress the independence movement. The law made it a criminal offense to own or display a Puerto Rican flag, to sing a patriotic tune, to speak or write of independence, and to meet with anyone or hold any assembly about the political state of Puerto Rico.

The fight for Puerto Rican independence continues today. In 1989, a letter was sent to President Bush from the leaders of the three main Puerto Rican political parties stating that since 1898, “the People of Puerto Rico have not been formally consulted by the United States of America as to their choice of their ultimate political status.” American courts decide what laws Puerto Rican follow; 90% of Puerto Rican industry is American-owned. These corporations don’t have to pay taxes while polluting the island. The largest American naval base, outside America, is stationed in Puerto Rico. The FBI operates overtly and covertly in Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rican people are still not free from American terrorism.

Cuba, 1898-1901

At first, we were damn near enthusiastic about helping a conquered country fight off its oppressive colonizers in the name of freedom. (This is ignoring the fact that the Cubans never needed nor wanted our help, and disregarding the fact that President McKinley refused the opportunity to have peaceful negotiations with Spain because such a solution would’ve denied America the prizes sought after.) But then, right as Cuba gained their long sought after and tirelessly won independence, America snatched it away from them.

When the Cubans freed themselves from Spanish rule, President McKinley couldn’t think of anything worse than the thought of the Cuban people having control over their own country. Our newspapers got to work right away, rewriting Cuban history and the story of the revolution to keep public opinion on the government’s side. We never thought of helping a fellow colony gain their freedom from a crown, only our own imperialist ideas in mind. Historian Samuel Eliot Morison said, “Any president with a backbone would have seized this opportunity for an honorable solution.” McKinley was terrified of an independent Cuba. Nothing was more horrific to him than a Cuba that would put its own needs first, a Cuba that wouldn’t do America’s bidding.

The Cuban revolutionaries who were posed to take power after the crown fell promised their people that they would establish social reforms to better the lives of everyone on the island, their first act, and the most notable, being land redistribution. This was McKinley’s worst nightmare, and American capitalists were terrified; they had more than $50 million invested in Cuba.

President McKinley then declared that America would rule Cuba under “the Law of Belligerent right over conquered territory.” This became known as the Platt Amendment; it gave the United States a way to run Cuba from DC using an indirect rule. America used numerous ways to keep its power and control over Cuba, their favorite being the imposition of tyrants who favored the interests of American companies and loved using military force to terrorize Cuban citizens.

Under this Amendment, America agreed to end their military occupation as soon as the Cubans accepted a pre-written constitution that gave the United States the right to maintain its military bases, veto any treaty between Cuba and another country, supervise the Cuban treasury, etc.

In essence, the Platt Amendment permitted Cubans to rule themselves as long as they allowed the US to veto any decision they made.

Of course, this Amendment was nothing but a formality, as American officials were sure to tell the Cubans that if they didn’t accept it, Congress would impose even harsher terms than the ones they already lived with in American-occupied Cuba.

Under these circumstances, Cuba has no other choice than to fall under American control, making Cuba one of the first countries we terrorized in the name of imperialism and capitalism.

Nicaragua, 1904-1910

At the end of the 19th century, political reform swept Central America. The ideals of socialism were appealing to many, appealing enough that America felt the need to take action. President Jose Santos Zelaya of Nicaragua felt these ideals more than others. As a result, Zelaya incorporated socialist principles into his own nationalist philosophy.

It was in 1893 when Zelaya first made a name for himself. Zelaya defeated the long-ruling conservative party with his comrades through an organized campaign that took the party down with incredible ease. A few months later, he rose to power as the country’s new leader.

President Zelaya had a remarkable plan, one that he was determined would put the country on the international stage. He built roads and ports, railways and government buildings, and built more than 140 schools. He paved streets and lined them with street lamps. He imported the county’s first-ever automobile. He legalized civil marriage and divorce. He encouraged business, promoted the union of five Central American countries, and embraced the idea of an interoceanic canal that the rest of the world had all but forced upon him.

The original plan was to have the canal built in Nicaragua; however, after businessman William Nelson Cromwell successfully lobbied for Congress to switch the project over to Panama, our attitude toward Nicaragua and its progressive President quickly soured.

The same people who had once said that President Zelaya “has given the people of Nicaragua as good a government as they will permit him” and that he had “ability, high character, and integrity” and was “the ablest and strongest man in Central America” who was “very popular with the masses, and is giving them an excellent government” now looked upon him in disdain. The American government now viewed Zelaya’s promotion of Central American unity as destabilizing and his efforts to regulate the American industries in his country started to look rebellious (even though both were once seen as symbols of his confident leadership and healthy nationalism).

It was 1904 when President Roosevelt changed American foreign policy forever. Roosevelt added the “Roosevelt Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, a piece of legislation that made otherwise unlawful intervention legal. The new edition now allowed the United States to intervene in any country in the Western Hemisphere that it judged to require intervention.

This law was immediately put to use against President Zelaya, who was hated amongst American businessmen. The time for overthrow came near in 1908 when Zelaya had threatened to cancel the La Luz concession (a partnership between an American company and the Nicaraguan government). Secretary of State Philander Knox, a corporate lawyer for many big businesses but significantly for La Luz and the Los Angeles Mining Company, two companies with lots of stake in Nicaragua, was eager to knock Zelaya from power.

Knox was both politically and socially close with the family who owned these companies as well, giving him even more incentive to destabilize an entire nation for decades to come. The last straw for Knox was President Zelaya forming treaties with European banks instead of American. Knox hated that Nicaragua was becoming less dependent on America, truly despised it, and immediately began working on a campaign to turn public opinion against Zelaya.

His goal was to paint Nicaragua as a totalitarian regime and orchestrated anti-Zelaya slander to be sent out to the press that defined Zelaya as “the menace of Central America” whose rule is a “reign of terror.” The defamation reached a peak during Taft’s presidency, when he decided that we would no longer “tolerate and deal with such a medieval despot.”

As it always is, the plan was to overthrow President Zelaya and put someone in power who would protect American interests, a puppet leader. Taft maintained that he was acting in the interest of American security and wanted nothing but to promote democratic principles, but that couldn’t have been farther from his true intentions. Taft didn’t care for spreading democracy. All he wanted was to defend the right of American corporations to operate as they wished to in Nicaragua. In the grand scheme of American history, Taft declared America’s right to force its idea of stability on foreign countries. Profits over people is a common theme in American foreign policy.

Thus started the Nicaraguan coup. Using America’s provincial governor General Juan José Estrada, a plan was formed.

On October 10, 1909, Estrada declared himself president of Nicaragua and appealed to the United States for diplomatic recognition. Estrada was incredibly well-financed, having La Luz and many other companies operating in and around Nicaragua sending him large amounts of money, nearing around $2 million.

Estrada and his rebels caused trouble around Nicaragua, attacking dozens of American foreigners and even blowing up a naval vessel carrying five hundred government soldiers.

Two of the rebels were convicted and sentenced to death. President Zelaya rejected their pleas for mercy, and they were put to death by firing squad on November 17th.

When news of the executions reached America, Knox jumped at the opportunity to find a diplomatic reason to set his coup into motion. He sent an angry note to the Nicaraguan foreign minister stating that America would “not for one moment tolerate such treatment of American citizens.” Knox then said that because Estrada had asked for diplomatic recognition, he was a belligerent, a nation or person engaged in war or conflict, as recognized by international law. This meant that any of his captured rebels were entitled to prisoner-of-war status. Killing two of them made President Zelaya a war criminal.

On December 1, Knox sent a letter to Washington D.C. for the Nicaraguan minister. The letter demanded that Zelaya’s government be replaced by “one entirely dissociated from the present intolerable conditions.” Nicaraguan school children still study this letter to this day.

On December 16, Zelaya submitted his letter of resignation. Knox’s letter made it clear that America wouldn’t stop until he was out of office (read the note here).

Zelaya’s successor, José Madríz, made it his priority to suppress Estrada’s rebellion. Madríz finally cornered Estrada and his rebels in May of 1910 and demanded that they surrender or face a harsh attack. However, before any fighting took place, the United States stepped in.

President Madríz thought he could negotiate with America about what they should do with the rebels, but he didn’t expect America to be so against his government. Madríz attempted to propose compromises, but American diplomats rejected them all. America would not be satisfied until the Nicaraguan government was utterly free of “Zelayist influence,” meaning completely free of liberal influence.

With nothing else he could do, Madríz resigned from office at the end of August. Estrada was now able to take power unopposed. He sent a letter to Knox to assure him that Nicaragua now held America in “warm regard” and was sworn in as president on August 21, 1910.

This was the first time the United States government had explicitly planned the overthrow of a foreign leader. Hawai’i was the result of American diplomats acting alone but later gaining the government’s support. Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines were known as ‘regime changes’ that were a part of a larger war. Nicaragua marked the first official American coup.

Guatemala, 1954

The reality of the Guatemalan coup that we as Americans have to face is how scarily intertwined a private company was with the United States government and the decisions made throughout the entire operation.

For half a century, United Fruit had raked in massive profits in Guatemala due to its ability to operate without government interference. The company claimed most of the good farmland, operated plantations on its own terms, and arranged for legal titles through one-sided deals with dictators. It never had to concern itself with taxes or labor regulations.

As long as this was able to continue, our government considered Guatemala a friendly and stable country. However, when a new type of government was introduced, and began to challenge the company’s authority, problems arose.

United Fruit thrived for so long because of the military dictatorship headed by Jorge Ubico. He called everyone a Communist whose social, economic, and political ideologies were more progressive than his own. He only trusted the army, the wealthy, and foreign corporations– clearly a man beloved by the American government.

Ubico gave United Fruit a 99-year-lease on a large area of land lining the Pacific and declared the company exempt from all taxes for the duration of this lease.

However, during the summer and fall of 1944, Ubico’s regime was overthrown by thousands of Guatemalan protestors who grew tired of his harsh rule. Then, a few months later, Guatemala held its first-ever democratic election, electing Juan José Arévalo as their president.

As President, Arévalo created a foundation of democracy in Guatemala, and used this to set up Guatemala’s first social security system, guaranteed the rights of trade unions, fixed a forty-eight-hour workweek, and imposed a modest tax on large landholders. These reforms aggravated United Fruit to no end. United Fruit had been navigating in Guatemala with its own rules for over half a century and resisted these new measures in any way they could.

When President Arévalo’s term ended, and Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán was elected president in 1951, the country saw its first-ever peaceful transfer of power. In his inaugural address, President Árbenz had three objectives for his term:

- To convert our country from a dependent nation with a semi-colonial economy into an economically independent country

- To transform Guatemala from a country bound by a predominantly feudal economy into a modern capitalist state

- To make this transformation in a way that will raise the standard of living of the great mass of our people to the highest level.

As soon as President Árbenz started to turn his goals into action, he found himself immediately clashing with the American companies that held monopolies in the Guatemalan economy.

He announced his plans of constructing an electric system that was publicly owned, thus breaking up the monopoly held by the America company Electric Bond & Share. Then he proposed building a new public transportation system connected to the capital, breaking up the monopoly held by International Railways of Central America, another American company. Finally, he challenged the vastly inequitable land ownership system that was the root of all poverty in Guatemala. Together, these three companies, again, all American, had more than $100 million invested in Guatemala.

Passed on June 17, 1952, the Agrarian Reform Law was hailed as the crowning achievement of the country’s democratic revolution. The law confiscated and redistributed all uncultivated land on estates larger than 672 acres and compensated the owners according to the land’s declared tax value. This directly threatened United Fruit, a company that owned more than 550,000 acres of land, with over 80% of it being uncultivated.

The Guatemalan government seized 234,000 uncultivated acres of United Fruit’s 295,000-acre plantation and offered $1.185 million, the value of the land the company had declared for taxes, as compensation. United Fruit rejected this offer and demanded $19 million, saying that no one took self-assessed tax value seriously.

While most Guatemalans considered the Agrarian Reform Law a step in the right direction, these three companies had controlled Guatemala for decades, and they and their stockholders despised Árbenz for implementing these new regulations.

President Árbenz was especially hated by John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State and the lawyer who represented all three of them. So, when United Fruit cried that Guatemala was falling under Communist influence, Dulles knew what to do.

Guatemala is the traditional leader of Central America, increasing America’s worries exponentially, as they were alarmed that any reforms that succeeded in Guatemala would quickly spread to other countries. Defending United Fruit and defeating Communism rapidly blended into one goal. How to achieve it? Overthrow President Árbenz.

Secretary of State Dulles was an exceptionally well-connected guy, to the point where it almost seemed like a combination of luck and manipulation. Dulles’s brother, Allen, was the CIA director and owned a large block of United Fruit’s stock. The Assistant Secretary of State Inter-American affairs, John Moors Cabot, and his brother, Thomas Dudley Cabot, the Director of International Security Affairs in the State Department, both were large shareholders. Head of the National Security Council, General Robert Culter, was United Fruit’s founding chairman of the board. The President of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, John J. McCloy, was a former board member. Everything was already in place; all Dulles had to do was light the fuse that would set everything into motion.

Turns out, Dulles didn’t even have to light the fuse himself. Instead, he passed the torch to Sam Zemmury.

United Fruit could only grow as big as it did because of Samuel Zemurray. After overthrowing the President of Honduras in 1911, he became one of the most influential people in Central America.

When Guatemala turned democratic in 1944, Zemurray met with a public relations expert, knowing the reformist government would be bad news for United Fruit. The expert suggested that the company launch a campaign to tarnish the image of the Guatemalan government, stating that this would weaken it and trigger a chain of events that would cause its collapse. When Zemurray learned of the Iranian Prime Minister, Mohammad Mossaddegh, nationalizing their oil in 1951, he decided to act on this suggestion.

It came in waves. First was the series of New York Times articles portraying Guatemala as falling under the ‘red’ influence. Then came the articles that warned about the emergence of a Marxist Dictatorship in Guatemala. What’s funny is that these wild claims can’t be considered libel because our government genuinely thought that President Árbenz was leading his country down the road of Communism. Even worse is that they thought this was somehow all a plan drafted in Moscow.

SECSTATE Dulles, in particular, had no doubt in his mind that the Soviet Union was actively working to mold life in Guatemala. Even though the Soviets had no military, economic, or diplomatic relations with Guatemala, and American leaders had nothing but their “deep conviction that such a tie must exist,” Dulles, as was the rest of the Eisenhower administration, was convinced that Moscow was behind every challenge to American power around the world.

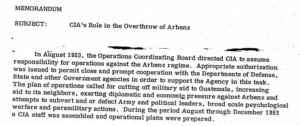

On the 3rd of December, 1953, the CIA authorized a starting amount of $3 million to set the Guatemalan coup in motion. With this $3 million, SECSTATE Dulles created a plan to stoke the fire of what would later be an attack made to look like a domestic uprising.

With his operation fully approved by the government, funded with $4.5 million, and the cooperation of the Honduran and Nicaraguan officials (two countries which had been overthrown by America and were now functioning with puppet leaders), the ball began rolling.

A propaganda campaign, a wave of destabilizing violence, American pilots bombing Guatemala City, and an American funded opposition leader (Guatemalan exile Carlos Castillo Armas) equipped with a rebel militia rolled over Guatemala. The country was in chaos. The American ambassador of Guatemala told the Guatemalan military commander that peace could only be restored if President Árbenz was removed from power.

With 500 Guatemalan exiles, American soldiers, and Central American mercenaries, Castillo Armas invaded Guatemala on June 18, 1954.

Guatemala had little-to-no defenses, as America had stopped supplying them with arms after the country turned democratic in 1944, and had pressured Denmark, Mexico, Cuba, and Switzerland to back out of their own arms deals as well.

On July 5, Castillo Armas was installed as president of Guatemala. His reign plagued the country with 40 years of civil war, death squads, torture, mass executions, and unimaginable cruelty, totaling over 200,000 deaths.

It’s not like we didn’t know about this brutality, either. The Reagan administration was well aware of the indiscriminate and genocidal nature of Guatemalan military operations when it approved of military aid in 1981

Guatemala was overthrown because its president sought to retake control of his country’s natural resources.

Cuba, 1959-1962

In 1959, President Fulgencio Batista was overthrown by a group of left-wingers led by Fidel Castro. Batista, backed by the American government for his anti-communist stance, fled Cuba after a seven-year dictatorial rule. Castro then launched a rebellious socialist state, severed Cuba’s strong relations with America, and gradually increased ties with the Soviet Union.

Castro then nationalized and seized all foreign economic assets (stock, bonds, etc.), raised taxes on American imports, and created trade deals with the USSR. In response, President Eisenhower cut the import quota for Cuban sugar, froze Cuban assets in America, imposed a trade embargo, and cut ties with the Cuban government.

This wasn’t enough for Eisenhower, though. In March of 1960, he and the CIA formed a plan to invade Cuba and dispose of President Castro and his regime. The CIA then assembled exiled counter-revolutionary Cubans to train and fund into a wing of the Democratic Revolutionary Front. This group was known as Brigade 2506.

Eisenhower’s term ended before he could see his plan through, but President Kennedy was ready to pick up exactly where his predecessor left off. In 1961, Kennedy deployed 1,400 CIA-sponsored Cuban exiles to overthrow the Castro regime. The plan went wrong almost immediately. When Brigade 2506 landed at the Bay of Pigs on April 17, 1961, the Cuban military, under the direct command of President Castro, overpowered and defeated them in two days.

This attack ended up strengthening Castro’s government. They began to openly announce their aim to embrace socialism completely and form closer ties with the USSR. This only fueled Kennedy further, thus began Operation Mongoose. The plan had a simple goal: remove Castro from power. Directed by the CIA and Department of Defense, Operation Mongoose consisted of many plans, leading to a 6-phase project that included political, psychological, and military sabotage, intelligence operations, and assassinations attempts on important political leaders, President Castro included.

Parts of the operation were set to destabilize the country and destroy trust in Castro. Preparations were made for an October 1962 military intervention, but it never occurred, leaving Castro in power and the Kennedy administration embarrassed. Castro continued to serve as the leader of Cuba until 2008 and died of natural causes at age 90 in 2016, successfully thwarting every U.S. attempt to have him killed or overthrown.

Nicaragua, 1978-89:

After our last stop in Nicaragua, we didn’t want to leave the country without royally screwing up any chance of a democratic future, hence leaving the National Guard behind.

The National Guard was left in the care of Anastasio Somoza, who then proceeded to take over the presidency with their help, and establish a family dynasty that ruled over Nicaragua for 43 years with unconditional American support.

The National Guard members, who America consistently maintained, passed their time with murdering of the opposition, torturing, raping, putting martial law into practice, massacring peasants, robbing, extortion, and running brothels.

The Somoza Dynasty was overthrown in July 1979 by the Sandinista National Liberation Front, which then established a revolutionary government. The Sandinistas inaugurated a policy of mass literacy, dedicated significant resources to health care, and promoted gender equality. Somoza fled to exile in Miami, worth $900 million, while ⅔ of Nicaragua were making less than $300 a year.

The American government, not wasting any time, authorized covert CIA support in Nicaragua to try to implement more moderate ideals into the Sandinista government. This was an attempt to prevent the spread of communism into Nicaragua before anything like it was even suggested. However, our idea of moderation was leaving the corrupt structure of the “Somoza apparatus” intact with some government-organized reform.

When the Sandinistas took power, the Carter administration authorized the CIA to fund and support anti-Sandinista groups. The United States also pressured the Sandinistas to include certain men in their new government, but, ultimately, these plans failed.

When President Reagan took office in 1981, he planned to make good on his campaign feelings for the new Nicaraguan government (he “deplores the Marxist Sandinista takeover of Nicaragua”) and quickly moved to suspend all assistance to the Sandinistas. However, he did send hundreds of thousands of dollars in covert aid to the Catholic Church in Nicaragua in an attempt to “thwart the Marxist-Leninist policies of the Sandinistas,” and authorized funds for recruiting, training, and arming Nicaraguan counter-revolutionaries.

The CIA also organized various attacks on fuel depots to wreck the Nicaraguan economy. American-sponsored anti-Sandinista groups caused extensive damage to crops. To prevent harvesting, they destroyed tobacco-drying barns, grain silos, irrigation projects, farmhouses and machinery, roads, bridges, and trucks. The American company Dole Fruit halted its operations in Nicaragua. The Nicaraguan fishing fleet was stuck at the docks from lack of fuel and an American blockade. The economy was in shambles all at the hands of the United States.

It was an all-out war on America’s side. We aimed to decimate any progressive social and economic programs initiated by the Sandinista government. We burned down schools and medical clinics. Anything was fair in the game against revolution.

The International Court of Justice found the United States guilty of aggression against Nicaragua in 1986. The Court ordered America to cease aggression and pay war reparations. In response, the United States declared that it no longer recognized the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice. Nevertheless, America continued with its terrorism.

To this day, reparations still have not been paid.

Middle East:

Iran, 1953

The story behind the Iran coup can be tied back to one thing: capitalism.

It all started with British imperialism. Since 1901, the British had a near-monopoly on Iranian oil. Called the Anglo-Iranian Oil company, the British only paid Iran 16% of the money earned from selling Iranian oil. The oil company made more profit in 1950 alone than it had paid Iran in royalties ever.

When Mohammad Mossaddegh was elected Prime Minister in 1951, his main goal was to nationalize his country’s oil, expel the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, and use the profits made from their oil industry to develop Iran.

Come springtime, both houses of the Iranian parliament unanimously voted to nationalize their oil industry. The entire nation celebrated. They viewed it as the dawn of a new era for Iran. If only that were the case.

Under this new nationalization law, the Iranian government agreed to compensate Britain for building their oil wells and refinery as a way to end their unfair contract on peaceful terms. Although, really, how much debt could Iran owe to the British after decades of them exploiting Iranian oil and making billions of dollars off of it?

Prime Minister Mossaddegh thought this action would not necessarily be well-received, but at least accepted by the British government; after all, the British had just recently nationalized their own coal and steel industries. He couldn’t have been more wrong.

Foreign Secretary Herbert Morrison stated: “Persian oil is of vital importance to our economy. We regard it as essential to do everything possible to prevent the Persians from getting away with a breach of their contractual obligations.”

For the next few years, the British did everything they could to make good on that statement. They considered bribing Mossaddegh, assassinating him, launching a military invasion, until they finally landed on orchestrating an old-fashioned coup.

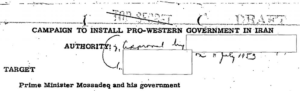

Before the British could get very far into their plan, Prime Minister Mossaddegh shut down the British embassy in Tehran, Iran’s capital. This didn’t stop the British, though. Instead, they asked the CIA to carry out the coup.

It was fairly easy to convince the CIA to take over the operation. All the British had to do was say Mossaddegh was leading Iran toward communism and everything else worked itself out. In exchange for their work, the British sent the CIA $1 million to use “in any way that would bring about the fall of Mossaddegh.”

The plan was simple: cut Mossaddegh away from the people and install a pro-Western government. This plan consisted of spending $150,000 to bribe journalists, editors, and Islamic preachers to “create, extend and enhance public hostility and distrust and fear of Mossaddegh and his government.”

The head man on the job? Kermit Roosevelt Jr., grandson of the man who kickstarted America’s era of regime change half a century earlier.

Using a network of Iranian agents, and spending massive amounts of money, Roosevelt created an entire web of lies surrounding Mossaddegh, spinning fake story after fake story, denouncing him with wild charges, to craft a wave of anti-Mossaddegh propaganda.

Religious leaders gave sermons calling him an infidel, newspapers were filled with libel, and cartoons were made that illustrated him as everything ranging from an agent of British imperialism to a homosexual.

When Mossaddegh learned of foreign intelligence agents bribing members of parliament to support action against him, he called for a national vote for a bill that would allow him to dissolve parliament and call for new elections.

Roosevelt, undeterred, drafted a new plan. He contacted Mohammad Reza Shah, the King of Iran, who was essentially rendered powerless after Prime Minister Mossaddegh’s election. Roosevelt wanted him to sign a royal decree that dismissed Mossaddegh from the position of Prime Minister and appoint General Fazlollah Zahedi as the new one. Roosevelt had a plan to follow this action, but, once again, Mossaddegh discovered the plot.

This, however, didn’t slow Roosevelt in the slightest. Through his time spent in Iran, he built up a far-reaching network of agents, and had paid them a large sum of money to keep their loyalty. Most of his roster hadn’t had the chance to shine, particularly the police and the army.

Determined to make a move against Mossaddegh, Roosevelt met with two of his top Iranian operatives, both of whom had excellent relations with the street gangs of Tehran. He informed them he wished to use these gangs to set off riots around the city. At first, the operatives didn’t want to help Roosevelt, as they felt the risk of taking action against Mossaddegh had become too great. Roosevelt offered both of them large sums of money as a bargaining chip, and when that didn’t work, he threatened their lives. The operatives got the gangs into place later that week.

Violence was rampant through the streets. The gangs broke shop windows, fired guns into mosques, beat up bystanders, and shouted, “Long live Mossaddegh and Communism!” Other gangs claimed allegiance to the Shah and attacked the first group. Funnily enough, both sides were working under Roosevelt; he just wanted to create the impression that Iran was descending into a state of chaos.

Mossaddegh sent police to restore order; he didn’t know the police were on Roosevelt’s payroll. Then, on August 19, 1953, thousands of paid demonstrators swarmed the streets to demand Mossaddegh’s resignation. The military and police joined the protestors, storming the foreign ministry, the central police station, and the army’s general staff headquarters.

As Iran’s capital descended into violence, soldiers stormed Mossaddegh’s house and arrested him. General Zahedi became Iran’s new prime minister. This coup restored the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, to absolute power and began 25 years of torture and repression. Ownership of the Iranian oil industry was returned to Britain, who split profits with America, giving themselves each 40% and splitting the remaining 20% amongst other countries.

Like the many other countries before it, Iran had fallen victim to American capitalism. The result of this coup led to not only the end of a democratic Iran, but also the emergence of a royal dictatorship that sparked an anti-American revolution.

Iraq, 1990s-2011

Iraq and the United States have a long, long history that dates back to the 1940’s but I will try to keep this brief.

In 1955, the United States included Iraq in the Baghdad Pact, an anti-Soviet defense alliance, along with Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, and Britain. This act, although it had its problems, had the potential to lead Iraq down the path of long-term stability after years of war with its neighboring countries and colonization by the British. This prospect went down the drain three years later after a military coup installed a new anti-Western regime

This revolt was not unique, as others followed in 1963, 1968, and 1979 and many others tried in between. Despite this internal struggle, Iraq arose as an independent power on the world stage. As soon as Iraq began a friendly relationship with the Soviet Union, America got involved.

From the start, American involvement in Iraq was based around having an ego war with the Soviet Union. We were there specifically to curb the spread of communism by preventing the rise of Soviet influence; meaning, we had no interest in the state of Iraq as long as it wasn’t communist. Every effort made by the Iraqi people to build a democracy was quickly shut down by the American government with the goal of keeping even the slightest hint of communism out of Iraq.

The early 70s brought an American nightmare to reality: Iraq nationalized its oil and partnered with the USSR. We then covertly armed and funded Kurdish rebels in an attempt to debilitate the Iraqi government, but they quickly solved this problem through negotiation with Iran. However, this act sparked a renewed sense of anti-American emotions. Enter: Saddam Hussein.

Hussein took power in 1979. He quickly suppressed all of his opposition, creating a faux sense of stability within the country, and waged war against Iran.

Iran-Iraq history and relations are long and complicated, so I’ll try and keep this on a need-to-know basis. In September of 1980, Hussein ordered a full-scale invasion of Iran, and captured 10,000 square miles of Iranian territory. Iran then successfully recaptured its territory, leading to a stalemate in 1982; however, the war carried on. By 1988, the war had created more than 1 million casualties.

President Reagan slowly involved the United States in the Iran-Iraq war, positioned our support on the side of Iraq. America was concerned with the spread of Iranian influence and anti-American sentiment across the region, leading Reagan to ignore Hussien’s political dictatorship and consider Iraq as a friendly world power that created a crucial wall against Iranian control. Ironically, Iraq already had enough of its own anti-American feelings brewing within its borders.

Reagan sent his special Middle East envoy to meet with Hussein and ask what America could do to help win the war. We provided crucial information about Iranian troops that allowed him to win battles that otherwise would’ve been a total defeat. We sold him $200 million worth of weaponry, gave him a fleet of helicopters, and loaned him $684 million to build an oil pipeline.

The Reagan Administration provided Iraq with economic aid, intelligence information about the Iranian military, repaired diplomatic relations, took Iraq off its list of terrorist nations, halted their protests against Iraq’s use of weapons of mass destruction against their opposition, and created the environment needed to ensure Iraq’s survival.

In 1988, a ceasefire was reached, and American officials hoped for the restoration of peace in the Middle East, with Suddam Hussein leading his country toward an era of prosperity. This hope was made on shaky ground at best, especially since America had refused to address Hussein’s multiple human rights abuses, aggressive behavior, and his totalitarianism. The hope of peace rested in the hands of Saddam Hussein.

Peace, of course, didn’t happen. After the Iran-Iraq war, Hussein intended to expand Iraq into Kuwait, leading to more conflict within the Middle East and with the United States

President H. W. Bush tried to deal with Hussein in a positive way, offering political friendship and economic incentive to try to convince him to reel in his expansionist behavior, while continuing to ignore Hussein’s dreadful human rights and foreign policy records.

(Friendship between America and Iraq began to fade when Hussein entered deals with the Soviet Union, but relations between the two countries were good until 1990.)

This proved to be useless, as Iraq invaded Kuwait in August of 1990. We opposed the occupation and Bush came up with two strategies: one for deterrence and one for military action.

For strategy one, Bush positioned soldiers in Saudi Arabia. For strategy two, Bush, with numerous allies, gathered military forces around Iraq and Kuwait. When Hussien refused to cave, five weeks of aerial assaults and a ground invasion followed. However, Bush stopped this advance, fearing it would lead to an expensive occupation.

On top of this, H. W. Bush, and his successor Clinton, included the United Nations in their containment plan against Iraq. They hoped to force Hussein into compliance with financial restrictions. Both Bush and Clinton used military strikes to punish Iraq for violating their containment plan, challenging Western warplanes (none were ever brought down), or hindering army inspections. The presidents thought the bombs would push Hussein to keep his power in check and erode his tyranny.

This plan continued until our invasion of Iraq in 2003 and largely achieved its purpose. Hussein was still in power, but he couldn’t do much without immediate military threat and the Iraqi economy was struggling. However, Hussein turned the situation around and gained sympathy through the suffering of his people (though both he and the airstrikes were equally at fault). Osama bin Laden cited these air attacks as one of his reasons for his war declaration against America.

When the second Bush came to office in 2001 he only had one thing, one country in mind: Iraq.

Bush saw Saddam Hussein as the guy who wanted to kill his dad, and in the aftermath of 9/11, he saw his opportunity for revenge. He desperately wanted Iraq to be behind 9/11, even going as far as to call a meeting a few days after the attacks to ask if Richard Clarke, the counterterrorism specialists for the past three presidents, and a couple of his aides would “go back over everything. See if Saddam did this. See if he’s linked in any way.” When told that it was confirmed to be Al Qaeda, not Hussein, behind the attacks, Bush replied saying, “I know, I know, but see if Saddam was involved. Just look. I want to know any shred. Look into Iraq. Saddam.”

Clarke warned the Bush administration about Al Qaeda very early on in Bush’s presidency. Clarke told them to make Al Qaeda a top priority because of the threat it posed to America. He was brushed off, and Iraq was cited as the biggest terrorism threat, even though Iraq hadn’t sponsored a single act of terrorism directed at America.

President Bush had an obsession. In order to justify it, he claimed that Hussein was building chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons, that he would soon attack everyone with “horrible poisons and diseases and gases and atomic weapons.”

This was a lie. Iraq’s military was shattered by an eight-year war with Iran and the economy was ruined by a decade of sanctions. Their weapons were old enough to be in a museum. Saddam Hussein was only a threat to his people, not the outside world.

In the months after the 9/11 attacks, Bush led America to the brink of war. Saddam Hussein was declared a mortal danger to national security, and it was implied that Iraq would provide weapons of mass destruction to terrorists. Action was finally taken in 2003 when America invaded Iraq.

It was brutal. With 125,000 American soldiers, 20,000 British soldiers, and 500 Australian soldiers, a combination of ground and aerial attacks left Iraqi forces scattered, the regime demolished, and the country occupied. However, this invasion showed the world that Bush had lied about the weapons of mass destruction that caused the war in the first place. Then the news of human rights abuses at the hands of American soldiers came out, quickly souring our image to the world.

The motivation behind the war with Iraq is a funny thing. Each administration member has their own reasons, and the reasons they told the public changed often, but it can all be watered down to a few core factors.

- Oil. Plain and simple.

- Money. Corporations made huge profits from the war and the aftermath, specifically Halliburton, an oil and infrastructure company that Vice President Dick Cheney formerly headed.

- The Pentagon saw the Iraq war as a way to prove their theories about how America could win future wars.

- They wanted to implement a pro-American Iraq.

- They wanted to show the world how powerful America had become.

- Democracy. This, of course, was a made-up motivation declared down the road. The Bush administration didn’t care about the spread of democracy, they just needed a righteous explanation to cover up their selfishness.

There was so much thought put into why we should start the war, but none put into what we should do after we win it. The Bush administration had zero plans for postwar occupation; so when a wave of violence further destabilized Iraq just a few short weeks after the fall of Hussein, the Bush administration had no idea how to handle it. All the plans they created failed miserably, and anti-American sentiment ran wild.

Suicide attacks, sniper fire, car bombs, and roadside bombs killed 300 American soldiers by December of 2003. The death number rose past 1,000 by September of 2004, and past 3,000 by January of 2007. Bush then increased the number of soldiers in Iraq from 120,000 to 160,000.

When Obama took office, he gradually rolled back on American military involvement in Iraq and promised to give Iraq’s future back to the Iraqi people. He ended combat operations in Iraq in August of 2010 and withdrew all combat forces in December of 2011.

The Iraq war took $1 trillion from the United States treasury, killed 100,000 Iraqis (the number is thought to be much higher), displaced 2 million from 2003 to 2011 alone, and ruined the country’s financial and physical infrastructure. Iraq is still unstable to this day.

Afghanistan, 1979-96

Not unlike the other Middle Eastern coups, American interest in Afghanistan surrounded the promise of oil. However, what makes Afghanistan unique is that the country has no actual oil on its territory. No mineral wealth or much fertile land either. What Afghanistan did have was location, roads connecting it to the markets of India, Iran, and China.

When the Afghan monarchy was overthrown in 1973, both the Soviet Union and the United States offered aid to the budding government. Then, when that government was replaced by a leftist coalition in 1979, trouble started.

A riot broke out in the then-capital Herat protesting against the inclusion of women in a literacy campaign that resulted in 20,000 deaths at the hands of the Afghan and Soviet governments. America grew concerned that the Soviets would take advantage of Afghanistan’s weakened state and attempt to make a push toward the Persian Gulf oil fields.

Islamic rebels diluted Soviet influence in Afghanistan. To America, this was the golden ticket they needed. After all, it wasn’t every day that anti-Soviet rebellions broke out; so, when one formed in Afghanistan, the CIA decided to give it covert support. They reasoned that the longer the rebellion lasted, the weaker the Soviets would become. This was the start of the largest and most expensive operation in CIA history.

Never once did the CIA stop and think about the long-term effects their actions might have, but there were certainly a lot of opportunities for this type of reconsideration. Opportunity number one was the fact that in order for this operation to take place, we would have to work with General Zai al-Huq, the Pakistani military dictator who ordered the execution of the man he overthrew and ran a network of agents around the world to buy outlawed nuclear technology. All of this was brushed aside in favor of intensifying the anti-Soviet rebellion in Afghanistan.

General Zai was propositioned and asked if he would turn his country into a base for this rebellion. The General agreed, but only if the CIA followed his strict conditions.

- The CIA will deliver weapons to Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency, not directly to the rebels.

- No Americans were to enter Afghanistan or have contact with their leaders.

- The Inter-Services Intelligence Agency would choose which leaders would receive CIA funds and artillery.

The CIA agreed to it all.

The director-general of the ISI, General Hamid Gul, commented after the war ended:

“The CIA knew exactly what their role was. They knew that we were handling the operations. We were in charge of the entire episode, and they were to provide the logistic support. They were not even allowed to travel into our own tribal areas, leave alone going into Afghanistan–so much so that they could not talk to Afghan leaders without my men, ISI men, being present.”

Then, in mid-1979, Communist leader Hafizullah Amin took power in Afghanistan as the Prime Minister. However, Amin addressed the Soviet Union with apathy and had met with American diplomats. This made the Soviets worry that Amin would abandon them. The USSR formed a plan to kill Amin and implement a more Soviet-friendly government. The plan worked. Afghanistan ceased to be ruled by a pro-Soviet government and was now under Soviet military occupation.

The Americans, of course, were thrilled at this change of events. Now they had the chance to directly attack the Soviets instead of indirectly through the support of a rebellion. The new plan now, as drafted by Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser Zbigniew Brzeziński, was “the withdrawal of the Soviet troops from Afghanistan. Even if this is not attainable, we should make Soviet involvement as costly as possible.”

President Carter welcomed this strategy, same with his successor Ronald Reagan, who immediately embraced Pakistan as a strategic ally and willfully ignored the atrocities of General Zia after taking office. Billions of dollars in aid was sent to Pakistan. What started as $60 million in economic and development assistance in 1979 quickly rose to more than $600 million per year in the mid-1980s. This doesn’t include the $3.1 billion in economic assistance and $2.19 billion in military assistance spent throughout the 1980s until 1990.

All of this money was delivered to the Pakistani government, who ultimately got to decide what to use it for. Nearly all of the aid, plus the American artillery, was handed over to the Inter-Services Intelligence Agency, which then distributed it out to leaders such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who found pleasure in leading chants like “Death to America!” with his followers, and other obscurantist warlords.

It was in the early 1980s when President Reagan started to believe that their rebel fighters in Afghanistan could defeat the Soviet soldiers if they had enough funds and firepower. In order to put this plan into action, a partnership with Saudi Arabia was forged.

Saudi Arabia was already heavily involved in Pakistan on their own. Substantial amounts of money was sent to General Zia to open religious schools that only taught the puritanical Wahhabi form of Islam where students weren’t taught subjects like history or science. These schools were marketed to the impoverished.

Saudi Arabia also had ties in America being a critical oil supplier. Reagan asked for Saudi support in Afghanistan by matching all American aid to the Afghan rebels. They agreed, and in 1986 the CIA sent $470 million to Afghan rebels followed by an additional $630 million the next year. All of which was matched by Saudi Arabia.

With sums of money as large as these, you’d think we would’ve been concerned with how it was being used, but no. It wasn’t as though we just never got to decide. We never even tried to play a role in how this money was used. All of these decisions were left up to Pakistan, and Pakistan had vastly different goals than we did. With American and Saudi money, Pakistan funded seven Afghan groups that were all some type of anti-Western who worked to destroy the leftists and nonreligious people of Afghanistan. Men were trained in modern techniques of ambush and assault and how to use all kinds of weapons ranging from snipers to delayed bombs at CIA-sponsored camps inside Pakistan. As one Afghan citizen put it: “you’re financing your own assassins!”

Here arises opportunity number two for the CIA to consider the future impact of their actions. As the war in Afghanistan went on, anti-American sentiment grew. Hijackers took control of an airliner in Lebanon and killed the American navy diver that was aboard. Other Hijackers seized a cruise ship and killed an elderly American passenger a few months later. Gunmen attacked airports in Vienna and Rome and killed four Americans. Back in Lebanon, the CIA station chief was tortured to death.

All of these events were highly publicized in America, yet no American leaders considered where the origins of this anti-American terror might’ve started, or where terrorists got the funds, weaponry, and training to carry out these attacks.

It’s thanks to America and the environment they created that Osama bin Laden was able to thrive. After serving as a rebel fighter in Afghanistan for a few months, Bin Laden convinced the ISI to grant him more important work. He was now in charge of receiving foreign militants and transporting them to training camps, a great place for him to meet other extremists.

Eventually, the rebel groups reached the point where they could challenge the Soviets; however, at this point the USSR thought of the war as hopeless, and began to pull back troops by the thousands until finally the last of the Red Army had retreated back to Soviet territory in 1989.

The Soviet Union collapsed a few years later after losing close to $200 million and 15,000 soldiers in the war. America was thrilled. To us, the war was never about Afghanistan. Who cared about the 1 million Afghans killed during the 1980s, or the 5 million who fled to refugee camps?

It didn’t take long for America to lose interest in Afghanistan altogether. Here comes opportunity number three: President Najibullah of Afghanistan warned America that if they didn’t remain active, then the country “will be turned into a center for terrorism.” Opportunity number four: State Department envoy Peter Thomsen reported threats from the Pakistan-backed rebel leaders who planned on taking out anyone in their way. These warnings were not taken seriously.

President Najibullah resigned after pressure from the rebel groups due to his inferior military support. The warlords formed a new government that quickly collapsed and broke out into civil war, with each side recruiting students from the thousands of CIA-funded religious schools in Pakistan. These recruits were religious students, or Talibs, so their movement was called the Taliban.

At the end of 1994, the Taliban had 20,000 troops, large amounts of weaponry, an endless supply of new recruits, and millions of dollars from the Saudi government at their disposal.

It was around this time that Osama bin Laden had returned to Afghanistan after staying in Sudan. With him, bin Laden brought Al Qaeda into the mix. He saw and recognized the Taliban as a group with beliefs akin to his own and gave them $3 million. In turn, the Taliban embraced bin Laden, and let him establish training camps in Afghanistan to teach militants terror tactics.

America remained on good terms with the Taliban, turning a blind eye to the horror that existed in the Taliban’s rule even in the early stage. This was because the American oil company Unocal wanted to build a $2 billion natural gas pipeline that would run across Afghanistan. America was willing to dismiss the actions of the Taliban if it meant Afghanistan was pacified enough for Unocal to build its pipeline.

On September 27, 1996, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, the United States, Osama bin Laden, and Taliban troops marched into Kabul. After this capture, Taliban militants ran wild. All visual imagery was now blasphemous. Photos, cameras, and TVs were destroyed. Music was considered evil. Radios and stereo equipment were destroyed. Alcohol, tobacco, dancing, and kite flying were all banned. Every possible right was taken from women. All of this was tolerated by American officials; nothing was more important than that pipeline.

A mere five weeks before 9/11, President Bush received and ignored repeated warnings that catastrophic attacks were coming, including the message from his intelligence advisers titled “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.” (read that message here).

Of course, 9/11 and the twenty-year war that followed wouldn’t have happened had we not armed and trained tens of thousands of right-wing radicals in the 1980s, and then ignored the signs when they made the move toward terrorism.

OTHER:

Hawai’i, 1893

How did we get a hold of Hawai’i? How did we ever get from the mainland to an island in the middle of the ocean? The answer: imperialism, colonialism, and an illegal overthrow of a government.

On January 17, 1893, the United States overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy. On this date, American businessmen and sugar planters forced Queen Lili‘uokalani from her throne. The Kingdom of Hawai’i dissolved two years after, and Hawai’i was (illegally) annexed as an American territory and eventual state.

When David Kalākaua took to the throne in 1874, he was compliant with the white missionaries and businessmen at first. He even signed a treaty that effectively turned Hawai’i into an American protectorate and essentially turned Hawaiian independence into a facade. This allowed the American government to build military bases on the islands, Pearl Harbor being one, and let planters operate as they pleased.

A few years later, however, King Kalākaua sought to reduce the power of the White Missionary Party. In 1887, a small group of Missionary Party members called the Hawaiian League fought back.

The Hawaiian League, led by Lorrin A. Thurston and Sanford B. Dole (yes, That Dole), crafted a new constitution that reduced the power of the king and gave voting rights to wealthy non-citizens, while also excluding Asians and restricting access for Native Hawaiians through land-owning and literacy conditions. The League, backed by an armed militia, threatened violence to push King Kalākaua to sign their constitution. This came to be known as the Bayonet Constitution.

When Kalākaua died in 1891, he was succeeded by his sister, Lili‘uokalani. On January 14th, two years into her reign, she proposed a new constitution, one that would restore power to the monarchy, make it so only Hawaiian citizens could vote, eliminate property qualifications, and cut the power of the nonnative elite.

This angered the white people of Hawai’i, enough so that 13 of them formed the Committee of Safety, whose goal was to overthrow the monarchy once and for all and then get annexed by America. Thurston and Dole had been waiting for an opportunity to attack the monarchy again. They set out a plan and got to work. Thurston wrote letters to D.C. in order to gain their support, claiming “general alarm and terror” had filled the island and that something had to be done, knowing fully that this was a lie. D.C. wrote back offering approval. The Committee of Safety rallied their troops.

On January 16th, Hawaiian Marshal Charles B. Wilson was given a tip that the Committee of Safety planned to stage a coup. Wilson tried to put Marshal Law into practice and requested warrants for the arrests of the Committee members, but because the Committee had such close ties in the American government (being that they were all white elites making large profits off Hawai’i), Queen Lili‘uokalani and her cabinet declined his requests, fearing that approving them would further escalate the violence.

On the 17th, a native police officer was shot trying to stop weapons from reaching the Committee’s militia. After that, the Committee of Safety put their coup into motion.

The militia, joined by 162 Marines and Navy sailors, surrounded the Queen’s ‘Iolani Palace in Honolulu. Queen Lili‘uokalani surrendered peacefully in hopes to stop any more violence against or deaths of her people.

There was an attempt made by Hawaiian royalists to restore the monarchy in 1895, but it didn’t succeed. Instead, it got Lili‘uokalani arrested for her alleged role in the coup and she was convicted of treason. After that, Lili‘uokalani (was forced to) agree to renounce the throne and dissolve the monarchy. Three years later, the United States annexed Hawai’i.

The Philippines, 1898-1902

What happened in the Philippines is almost the prime example of American imperialism.

Businessmen had become nothing short of bewitched by the idea of selling their products in China. After losing in a war with Japan in 1895, China was unstable and unable to resist the American invasion; but, first, America had to find a piece of land in between America and China where they could set up camp. This is where the Philippines comes into play.

At the time, most, if not all, Americans had no knowledge about the Philippines: our government couldn’t even point it out on a map. All we saw when we looked at the country, a country that housed 7 million people, was the commercial opportunity. President McKinley stated that “American statesmanship cannot be indifferent” when it came to the possible profits to be made.

McKinley didn’t see the Philippines as a country, he barely saw them as people, simply a stepping stone in the process of increasing American profits.

In 1898, the Philippines were nearing the end of a war with the Spanish, fighting desperately for their independence after living 300 years as a colony of Spain. The United States, with hidden intentions like always, promised to help free the Philippines from colonial rule and aid them on their road to independence. This, of course, never happened.

Promises were made, but American officials claimed they never uttered such words. President McKinley told Congress in a message asking for ratification of the Treaty of Paris, that “we could not turn [the Philippines] over to France or Germany, our commercial rivals in the orient, that would be bad business and discreditable.” Showing, again, that McKinley truly only saw the Philippines as a means to an end, a place we had to obtain in order to further our own agenda.

America, however, had no idea who they were dealing with. They had no idea they set foot on the soil of the country that hosted the first anti-colonial revolution in the modern history of Asia.

It was like Manifest Destiny part 2. President McKinley claimed it was the will of God that gave him the idea to build military bases in the Philippines on top of taking control of the whole country, all 7,000 islands and 7 million people of it.

McKinley also famously stated that “there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos and uplift them and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could for them, as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died.” Genuinely Manifest Destiny part 2.

McKinley presented an “executive letter” that proclaimed American sovereignty over the Philippines. Filipinos, however, had no idea this was taking place. They had already elected a constituent assembly (like our continental congress), published a constitution, and, on January 23, 1899, declared themselves the Republic of the Philippines with Emilio Aguinaldo as the first president. Only 12 days later, the Republic of the Philippines declared war on the American troops stationed on their island.

It wasn’t hard for America to find people willing to ship themselves off to a foreign land to fight against a perceived enemy whose motivations they were ignorant of. Soldiers landed on the shores of the Philippines by the tens of thousands.

While the Filipinos were forced to resort to fighting the war guerrilla-style, the Americans had the luxury of going about it in a different manner. We decided to fight this war through a means of indiscriminate brutality.

On March 23, 1901, President Aguinaldo was captured by American forces and coerced into accepting American sovereignty as well as pleading with his people to give up on their fight.

The fighting continued. In September, rebel fighters invaded the American position held on the island of Samar. This set off what is considered some of the harshest countermeasures ever ordered by American officers. Reports of imprisonment, torture, and rape were common.

Colonel Jacob Smith is on record ordering his men to kill everyone over the age of ten and to turn the Philippines into a “howling wilderness.” He said, “I want no prisoners, I wish you to kill and burn. The more you kill and the more you burn, the better you will please me.”

American commanders placed restrictions on foreign journalists and reporters to make sure news of what was actually happening would never reach home. The restrictions weren’t lifted until late-1901, and it was only after this fact did Americans learn how and why the war was being waged.

On July 4, 1902, President Roosevelt declared the Philippines pacified and ordered his troops to pull out. In a sense, he had legitimate standing to think of the Philippines as pacified, after all, we had killed or captured all of their important leaders, putting an effective stop on resistance.

By the end of the war, America had lost 1,500 soldiers. The Philippines, on the other hand, lost 20,000 soldiers and another 200,000 civilians to combat, starvation, and disease.

To Filipinos, this war is remembered as some of the bloodiest years in their history. Americans soon forgot this war ever took place.

1945-54

During WWII, Japan invaded the Philippines. Leftist forces, the Huks, banded together, obtaining arms and ammunition, and began recruiting and campaigning for support in the fight against the Japanese.

The Japanese tortured and murdered many civilians to try and gain information about the Huks and their members. This brutality only led more people to join the Huks in their fight against Japan.

By the end of this war, the Huks had established a democratic socialist government; however, the United States military (who had, again, invaded the Philippines while they were fighting off Japanese invaders) refused to acknowledge this government and leave the islands.

America demanded the Huks surrender their weapons to the U.S. armies stationed in the Philippines. Their refusal led to a decade-long war between the Philippines and America, with America ultimately taking the win.

With the rebellion crushed and leaders scattered, America was free to occupy the Philippines as they pleased, including installing a series of puppet leaders that favored American interests. This led to the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos.

1965

Ferdinand Marcos was elected President of the Philippines in 1965. Immediately following his election, Marcos closed Congress, suspended the constitution, canceled upcoming elections, and ordered the arrest of 30,000 of his opponents.

Marcos had a very particular style of ruling. Campaigns of torture, rape, and murder held his regime in place. American presidents, of course, had interacted with President Marcos, and while none of them held him in ‘much esteem,’ they also didn’t do anything about him.

Nixon, Carter, and Reagan all maintained friendly relations with Marcos. The U.S. gave his regime billions of dollars in military aid, most of which was spent on brutal campaigns against his opposition, rebel groups and peaceful protesters alike.

This behavior was ignored by America in favor of keeping hold of the Clark Air Base and Subic Bay Naval Station. These military bases were the foundation of American military power in Asia. We were eager to do anything possible to maintain this power. President Reagan even stated, “I don’t know anything more important than those bases.”

Once again, America prioritized power and profits over people.

During our reign in the Philippines, we never attempted to develop any kind of social programs that would’ve moved the country down the road to long-term stability. The fear of losing our military power led us to support a dictatorship that was much more invested in stealing money from its people than taking steps to move the country forward.

Vietnam, 1953-63

The Vietnamese were engaged in a war for their independence when America came along. France was determined to maintain its colonial power over Vietnam, but, after years of fighting, the French were worn down, and concluded that they had to let go of Vietnam and work toward peace.

Early in 1954, the French and Vietnamese leaders met in Geneva, Switzerland, with negotiators from China, the USSR, Britain, and America. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles led the American part of the delegation. He hoped to prevent the countries from settling on an agreement, but had little success and left after a week.

The remaining representatives agreed on a temporary division of Vietnam. Communists would have the North with the capital of Hanoi, and the former French allies would take the South with the capital of Saigon. Then, in two years, nationwide elections would take place in which the North and the South would reunite. While these two years panned out, no outside power was to send arms or soldiers into Vietnam. This, of course, didn’t happen; and this, of course, was due to the United States.

Many Vietnamese citizens assumed the Communist Revolutionary Hồ Chí Minh would be elected president in their 1956 election. After all, he had led their country into battle and defeated a far more powerful enemy. SECSTATE Dulles wasn’t going to sit by when there was a possibility of Vietnam voting for a Communist president to lead to their reunification. He immediately drafted a plan to undermine the Geneva agreement with one goal in mind: make Vietnam’s division permanent.

When the Head of State Bảo Đại appointed Ngô Đình Diệm as the new Prime Minister of South Vietnam, Dulles jumped at the chance to have an inside man. Pro-French and anti-Communist, Diệm was exactly who Dulles needed.

With Diệm in power, he and Dulles decided not to hold the scheduled reunification election. Instead, they had a (government-controlled) referendum, a general vote on a single political question. The question concerned South Vietnam leadership, the classic ‘who did people prefer’ question. Diệm won 98.2% of the vote. Bảo Đại was removed from power, and Diệm made himself Chief of State, quickly imposing a new constitution that gave him complete authority and ruled South Vietnam with his family.

America was determined to keep the division permanent, but North Vietnam had other plans. Hồ Chí Minh and his comrades launched their third anticolonial war. Their campaign aimed at “the elimination of the U.S. imperialists and the Ngô Đình Diệm clique.”

Then SECSTATE Dulles died, and President Eisenhower completely lost interest in Vietnam. So much so that he didn’t even mention the country when briefing President-elect Kennedy on world troubles. Kennedy, however, didn’t lose interest in Vietnam. The number of American soldiers in South Vietnam rose from under 900 to 18,000 under his orders.

President Kennedy sent jet fighters, helicopters, heavy artillery, etc., to South Vietnam, violating the Geneva agreement. None of this helped the battle in our favor.

Diệm had issues with the growing role America played in his country, complaining that the American presence only worsened the situation. Our government didn’t listen, and troops continued to pour in.

Then Buddhist priests began to set themselves on fire in protest of the corrupted South Vietnamese government in the middle of it all. Fearing that Diệm’s corruption would cause the South population to admire the Communist ways of the North, the Kennedy administration formed a plan: overthrow Diệm.

We didn’t care about Diệm and his family’s brutal treatment of their citizens; we only cared that they might turn to Communism if we left Diệm in power.

They planted an anti-Diệm group, and, with the approval of Kennedy, the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, and the CIA, another regime change was on its way. Nothing was worse than the idea of losing our position in Southeast Asia.

With the cooperation of South Vietnamese generals, the plan was set in motion. They circled and stormed Diệm’s house and coerced him into resigning. Diệm and his brother were found dead the following day. This was in 1963. We didn’t pull out of Vietnam until over a decade later.

The Pentagon Papers admit to all of this:

“For the military coup d’etat against Ngo Dinh Diem, the U.S. must accept its full share of responsibility. Beginning in August of 1963 we variously authorized, sanctioned, and encouraged the coup efforts of the Vietnamese generals and offered full support for a successor government. In October we cut off aid to Diem in a direct rebuff, giving a green light to the generals. We maintained clandestine contact with them throughout the planning and execution of the coup and sought to review their operational plans and proposed new government. Thus, as the nine-year rule of Diem came to a bloody end, our complicity in his overthrow heightened our responsibilities and our commitment in an essentially leaderless Vietnam.”

We remained in Vietnam until 1975; 23 years wasted, 58,000 Americans and almost 4 million Vietnamese dead. All for what?

Why Does it Matter?

America always has been, and always will be, the world’s biggest threat.

We have close to 800 active military bases spread across over 80 different countries, yet there isn’t a single foreign military base in America.

It matters because our actions have consequences. America and America alone is the mastermind behind the Taliban, is the reason for a destabilized and war-ridden Middle East; is responsible for the genocide of Guatemala’s native population, is the cause of the civil war that wracked El Salvador’s economy and killed any sense of a functioning democracy.

It matters because the consequences of our actions are still felt today. Each country we’ve invaded, overthrown, meddled with is facing problems that are directly connected to our military involvement.

I’m not even scratching the surface of the history of American terrorism, and I’m absolutely certain that I’m missing details on the coups I’ve written about. Below I’ve included an A to Z list of countries we’ve involved ourselves with for the sole reasons of American economic gain and anti-communism. Click on one, two, three, any number of the links to learn more about the havoc we’ve wreaked all over the globe. Some links go further in-depth than others, and I encourage everyone who’s read this far to learn everything they can about the horror we’ve put the world through.

As American citizens who benefit from the terrorism our country takes part in, I believe it’s our responsibility to educate ourselves and to take the time to learn about the current states of the countries we’ve ruined. The only way we can go from here is forward, and the way to do that is through an educated public.

A definitely incomplete list of countries not mentioned in the article:

Albania, 1949-53

Argentina, 1976

Bolivia, 2019

Brazil, 1961-64

Cambodia, 1955-73

China, 1945-49

Chile, 1964-73

Dominican Republic, 1960-66

East Timor, 1975-2006

El Salvador, 1980-92

Germany, 1950s

Ghana, 1965-66

Grenada, 1979-84

Guyana, 1953-64

Haiti, 1987-94

Israel, 1966-present

Italy, 1947-48

Japan, 1950s-1960s

Korea/South Korea, 1945-53

Laos, 1950-69

Panama, 1969-91

The Congo/Zaire, 1960-65

Ukraine, 2014

Stan Smith • Aug 26, 2022 at 8:35 pm