Somatic and Germline Gene Editing

Photo Source: Pixabay

October 13, 2022

Genome editing has the potential to treat diseases like cancer and AIDS, or to edit the genes of human embryos, but how is this technology regulated?

Germline cells are reproductive cells while somatic cells are body cells other than sperm and egg cells. Edits of somatic cells are isolated to certain tissues and are not passed through generations.

The first germline-edited babies, twin girls Lulu and Nana, were born in China in 2018. Their genes were edited with the intent of making them HIV resistant. The unpublished manuscript of He Jiankui, the biophysicist who created the twins, reveals troubling insight to the experiment.

A small percentage of people are born with the CCR5 Delta 32 mutation which can make them naturally immune to HIV infection. Jiankui’s data claims that he reproduced that mutation when in reality, he created a new mutation.

Since the edits Jiankui and his team made are not identical to the natural mutation, it can not be known if Lulu and Nana are even HIV resistant. The effectiveness of the gene editing could have been tested before the embryos were implanted, but they were not.

When asked about editing her own children’s DNA, Pamela Endyke, the head of Pentucket’s Science Department, responded, “I wouldn’t edit genes on my own children unless it was for a very detrimental health issue.”

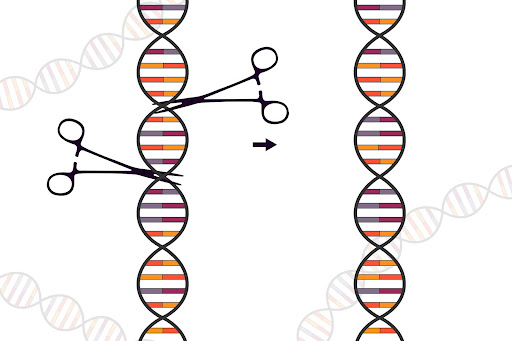

The new technology being used to edit DNA is called CRISPR. Two parts make up CRISPR, a guide RNA and a DNA-cutting enzyme called Cas9. The guide RNA matches up with the target gene’s DNA then Cas9 cuts the DNA. Genes can be inactivated, new segments of DNA can be added, or single DNA letters can be edited.

One risk of gene editing is off-target modifications occurring. Even if guide RNAs are designed to target a specific genetic region, it is possible for the wrong DNA to be cut, creating unwanted mutations in the genome.

Another concern is that genome editing will only be accessible to the wealthy. This will worsen the disparities in health care. Some worry that in the future genetically editing human embryos will lead to eugenics.

The Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing is scheduled for March of 2023; experts will gather to discuss possible regulations of gene editing. When asked about the ethics of human genome editing, Mrs. Endyke said, “it needs to have a little bit of governance as to how it’s used.” One concern is that genome editing will be regulated differently depending on the country.

Germline editing, the alteration of reproductive cells so that the change is heritable, is highly regulated in China after the birth of the twins. Implanting genetically engineered embryos or allowing them to develop past fourteen days is prohibited. In the United States, federal law prohibits the use of federal funds for germline editing, but there are no laws prohibiting germline editing through private funding.

There are hundreds of active clinical trials in the United States involving somatic cell gene editing. The Department of Health and Human Services must approve the clinical trials. In China, somatic cell gene editing is only lightly regulated; clinical trials only need to be approved by an ethics committee of any hospital.

Time will show if gene editing will become a common treatment. Regulations are expected to be updated at the Summit.