Back To Vesuvius: 79 A.D.

(Photo Source: Pierre-Jacques Volaire, Eruption of Mount Vesuvius, 1777)

December 13, 2022

It is another beautiful day and you are lounging by the sea with the warmth of the sun falling on your skin. Then, a resounding boom roars, shaking you into reality. Looming clouds of thick, black smoke fog over the horizon. The sun’s glow becomes ghastly as ash, rock, and gas spew from a volcano in the distance. It is the year 79; you are in the midst of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

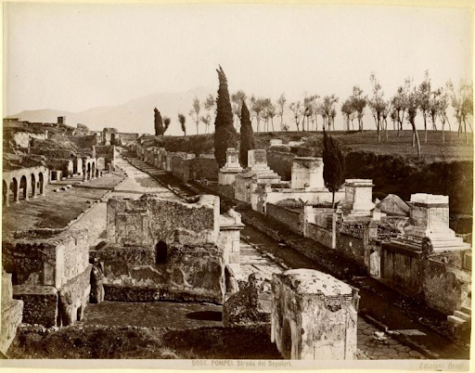

Pompeii and Herculaneum

Near the base of Mount Vesuvius, at the bay of Naples, the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum flourished. During the time of the early Roman Empire, approximately 12,000 people lived in Pompeii, while only about 5,000 lived in Herculaneum. Pompeii was full of merchants, manufacturers, and farmers who used the rich soil of the region for vineyards and orchards. Herculaneum, on the other hand, was a favored vacation destination for the wealthier Romans. The city boasted lavish villas and grand fountains. Both cities prospered, yet no one would have thought that the fertile earth was the product of earlier eruptions of Mount Vesuvius.

(Photo Source: Louis S. Glanzman)

In 1748, the lost Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were rediscovered. With excavations continuing to this day, scientists have been able to unveil the events that ensued on the tragic day of the volcano’s explosion. An unprecedented archaeological record of the life of these ancient civilizations is due to the startling preservation from the volcano’s ash.

What Happened?

Much of what is known about the eruption of Mount Vesuvius can be attributed to the account of a 17 year old boy, Pliny the Younger. He was also nephew to the Roman naturalist, military campaigner, and writer Pliny the Elder.

According to the only known written record of this event, the eruption lasted 18 hours. The city of Pompeii was buried under 14-17 feet of ash and pumice; Herculaneum was buried under more than 60 feet of mud and other volcanic substances. The nearby seacoast was drastically changed as well.

Pliny the Younger witnessed the scenes of panic and death from a higher vantage point in his villa across the bay of Naples in Misenum.

The following recounts Pliny the Younger’s experience of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

“It was not clear at that distance from which mountain the cloud was rising (it was afterwards known to be Vesuvius); its general appearance can best be expressed as being like an umbrella pine, for it rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches, I imagine because it was thrust upwards by the first blast and then left unsupported as the pressure subsided, or else it was borne down by its own weight so that it spread out and gradually dispersed. In places it looked white, elsewhere blotched and dirty, according to the amount of soil and ashes it carried with it.”

“Ashes were already falling, not as yet very thickly. I looked round: a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood. ‘Let us leave the road while we can still see,’ I said, ‘or we shall be knocked down and trampled underfoot in the dark by the crowd behind.’ We had scarcely sat down to rest when darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night, but as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room.”

“You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognize them by their voices. People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore.”

“There were people, too, who added to the real perils by inventing fictitious dangers: some reported that part of Misenum had collapsed or another part was on fire, and though their tales were false they found others to believe them. A gleam of light returned, but we took this to be a warning of the approaching flames rather than daylight. However, the flames remained some distance off; then darkness came on once more and ashes began to fall again, this time in heavy showers. We rose from time to time and shook them off, otherwise we should have been buried and crushed beneath their weight. I could boast that not a groan or cry of fear escaped me in these perils, but I admit that I derived some poor consolation in my mortal lot from the belief that the whole world was dying with me and I with it.”

Aftermath

The remains of 2,000 men, women, and children were uncovered at Pompeii. The victims passed from asphyxiation, the ash soon covering bodies and preserving their outlines. These bodies deteriorated to skeletal remains, leaving molds of hardened ash behind. When discovered by archaeologists, the molds were filled with plaster to reveal the details of the volcano’s victims. Herculaneum’s human remains were not found until 1982, bearing evidence of the horrifying deaths that occurred thousands of years ago.

The cities were found as they were. Ordinary objects frozen in time, the stories of everyday life revealed.

With its last eruption in 1944 and its last major eruption in 1631, Mount Vesuvius is the only active volcano on the European mainland. However, there is expected to be another eruption in the near future which may prove devastating for the hundreds of thousands of people living in the volcano’s death zones.

The End of The World

Pliny the Younger’s record of this tragic event not only provides a gruesome scene, it also captures the intense fear and emotions of Mount Vesuvius’s unfortunate victims.

Petrifying shrieks, wails, and shouts resonated throughout the cities. Some cried out to loved ones, others prayed in terror of death. People looked to the gods for guidance, but many could no longer fathom a savior; especially not one who let their entire lives become buried beneath perpetual darkness.

What Would You Do If Your World Was Coming To An End?

Would nothing matter to you anymore, or would you try to fulfill these last moments meaningfully? Pentucket’s senior students have a few ideas.

Olivia Bartholomew says, “Honestly, I would probably be freaking out in the moment. I would call my parents, I would cry. I’d want to be with my family and friends so we could all die together.”

Courtney Sylvanowicz adds, “I would spend that time meaningfully, to make sure my parents are okay. If I died, it would be really hard for my parents and I would want to be with them for those last moments. I feel like I might even confess some things, just because it’s the end of the world so why not.”

“I would spend my remaining time meaningfully. I would likely say my goodbyes to friends and family, then I would attempt to fulfill a dream or bucket list item that was not previously possible. Whether that may be to see a certain place, experience something, or anything else,” says Bradley Latham.

While the end may one day come, right now there is all the time in the world. Live meaningfully if you so choose, because you never know what comes next. Live each day like it is your last.

Libby • Dec 13, 2022 at 9:31 pm

It is evident why this event holds so much significance in world history: it is so uniquely both tragic and magnificent. The horror that ensued that day was unimaginable, yet through the preservation of the city and the letter written by Pliny, we as a society are able to understand and deeply empathize with the citizens of Pompeii all those years ago. The fact that Pliny’s experience is the only known first hand account of the eruption is dumbfounding considering how detail-rich his writing is; it seems as though he knew his letter would be the only piece of documented historical evidence that we would have centuries later. While the people living at the base of Mount Vesuvius certainty did not deserve the fate they suffered, what they left behind has become such a monumental relic that will forever be marveled at.