It’s a cold and gloomy day in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

September is over, October is here, and November awaits us. Summer is now a faded memory only remembered when the sun warms us.

I step out onto the brick covered sidewalks from my car and take a deep breath of the smoky sky.

It’s quiet for the downtown area, which is normally bustling with locals and tourists everywhere.

Along the water, the fog is so thick you can’t even see the enormous boats docked up against the pier.

I make my way onto Newburyport’s Rail Trail, a popular site for couples, runners, friends young and old, moms, and anyone in need of a cigarette break.

Right in front of me, I come across Oldies Marketplace, an antique and collectibles store that is ten times better than any other store in downtown Newburyport.

The second I step into the store, a warm and comforting feeling comes over me.

As big as a flea market yet small enough to still be considered a thrift store, Oldie’s has a familiar scent of the past that greets me walking by the rows upon rows of antiques.

Kitchen tables, light fixtures, photo frames, chairs, paintings, curtains, carpets, rugs, clothing, shoes, China sets, doorknobs, and beyond. Oldie’s has everything you could possibly think of that turns our houses into homes.

I make my way over to the painting and photograph section. It’s a little frightening, having all these eyes peer down at me, but it’s fascinating nonetheless.

There, on a table with a Boston Globe paper from 2002, are little straw baskets with dozens of photographs from the twentieth century in the local Cape Ann area.

I pick up a Newburyport class photo from an unnamed school. Youthful children in red and gold uniforms and little petticoats smile back at me. Their teacher, in dark, wooly clothing, stands off to the side, smiling alongside them.

Their faces glow with a kind of innocence that died long after them.

There’s more than just class pictures here. Weddings, family portraits, self-portraits, baby photos, engagement photos, and birthday photos–every single monumental milestone in life available for the fair price of two to three dollars.

Two to three dollars. That’s what these people and these memories are worth.

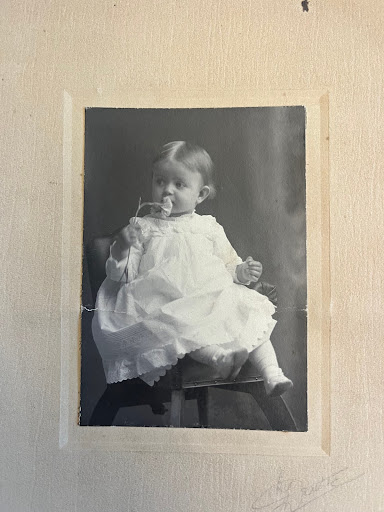

As the realization is starting to sink in that I am watching the lives of these people unfold through mere photographs, I stumble across a worn baby picture of a young girl in a white dress holding a small daffodil in her hand.

The photograph sits with the rest of the unclaimed photos. The cracking on its paper tells me it has seen better days.

Her name was Virginia Davis Perley, and she lived right over the Merrimack River in Ipswich, Massachusetts. I don’t know anything else about her besides the fact that she was ironically the grandmother of the older cashier who checked out my photograph.

Though I only know three key details about her in a black and white photograph, the image of the daffodil in Perley’s hand as she keeps her body still while her eyes dance off-camera gives me a feeling I can only explain in a series of Carrie-Bradshaw style questions.

If all we are worth in the end is two dollars, then why do we spend so much time obsessing over perfecting ourselves in every aspect of our lives?

What is the point of sacrificing ourselves, our careers, and our education for others if all we are in the end is to end up unknown, unnamed, and unwanted?

Should we continue to push ourselves to be disciplined, rigorous, and strict with ourselves?

Then again, do any of the “meaningful” events in our lives truly hold any more value than constantly striving for perfection?

I ponder these questions over and over in my head as I pace around the store while my brain reverts back to modern times. The sound of Apple Pay tapping the screen and Snapchat notifications ring in my ear.

It would be a lie to say that I don’t use either of those technologies, but who can blame me?

If we had been alive in the twentieth century, you definitely wouldn’t hear Snapchat or Apple Pay, but you’d hear its predecessor: the clatter of coins and small-town gossip.

How can we blame ourselves for being modern when the luxuries of technology we are able to afford today hadn’t been something that was even considered in the past?

Has technology corrupted us?

Have material objects and the pursuit for amassing wealth gotten in the way of appreciating life for how it is?

Or, have we always been corrupted?

Think about it. If we are to criticize our modern society, then we might as well find it appropriate to bring up how corrupted the history of America and the rest of the world is. People of color, women, and the LGBTQ+ community were all oppressed and dehumanized for hundreds of years.

Though those same groups are still oppressed today, we combat it, from protests and petitions to marches and taking action against those who want to unjustly discriminate against certain groups.

So maybe we aren’t too different from the past, maybe we are completely different, or maybe we are somewhere in between.

But if we want to call ourselves “evolved” or an “advanced society,” then we need to consider that in order to do so, we have to open our eyes to issues that are still actively present in our everyday lives.

And we need to do something about those issues.

For, if we just end up as a two dollar photograph in an antique store in the end, we may as well spend our life here making an impact on our world rather than just having an impact on ourselves.

You can be so well-educated with a good, well-paying job and yet still lack complete empathy for others and the world around you.

Consider the choices you make each day. Of course you can strive for success. No one ever said you couldn’t. Being successful is much more than the number or letter we are given to define our work.

True success is when we work to not just enjoy life, but to appreciate it in every single aspect and make it a priority to care about the world we live in and what goes on in it, too.

I check out Perley’s photograph at the register. As I head back outside, I am not left with doubt nor depression. I didn’t gain anything, but I didn’t lose anything, either.

I think about Virginia a lot.

What was she like?

Who was she? An advocate for change? A bystander?

I’ll never know for sure. And maybe that’s okay.

If I have learned anything from my time studying Perley’s photograph at Oldie’s, it’s that I must stop hyper-fixating on small details and focus on painting a bigger picture that is mine to study: my life.

And it will have meaning to me because it’s mine.

It’s everything, and it’s nothing, and maybe it’s something in between, too.