Is It Time to Retire Racist Books From Our School?

March 10, 2021

With growing social tensions and hyper-awareness towards racial injustice, our society has vocalized the growing need to teach anti-racism to children in school. Some schools across the country have chosen to show solidarity with this movement by removing books that include strong racist language and themes from their curriculums. These books include Huckleberry Finn, To Kill a Mockingbird, Of Mice and Men, and more. While the movement to remove these books has certainly been applauded, some school districts have shown objection to the idea of removing literature like these from education. This debate really intrigued me, as I have often questioned whether or not we should still be reading books like these here in Pentucket. I thought the best way to find an answer to this debate was to ask some teachers and students around the school how they feel about the topic.

Context Matters

When asked if it was important to teach issues such as racism and racial issues through literature, the general consensus shared by Pentucket teachers and students was almost unanimous: context is everything.

“I think that it is so important that we teach these topics to kids in high school, but I think it all depends on how the teacher delivers the lesson. Context is the most important thing for teaching stuff like this,” says AJ Thistlewood, a junior here at Pentucket.

“This is a tough one,” answered English teacher, Mr. Casey. “It would depend on the specific literature being used and the way it is presented. Context is everything”.

It is true that context is incredibly important for teaching about race in the classroom, as it is an issue that needs to be handled in an incredibly delicate manner. Along with the importance of context, another concept that I heard a lot throughout my interviewing was the deep significance of connecting one’s own experience with the text in which they are reading.

“The most valuable aspect of the English classroom is experiencing the lives of others vicariously through texts and discussion in order to understand how to interpret one’s own experience,” says English teacher Mrs. Miner. “To understand the truth of our beliefs, we need to engage in discussions with alternate points of view, thus necessitating the integration of a diversity of views in the texts we study in English class.”

So if context is everything, should we continue to read books with intense cases of normalized racism?

Controversial Books

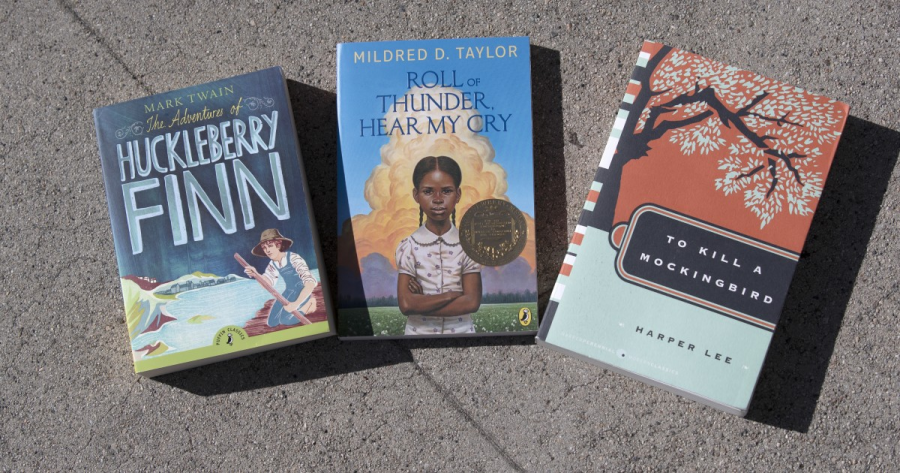

Let’s look at the specific books in question. Huckleberry Finn, Of Mice and Men, and To Kill a Mockingbird are all classic pieces of literature, but one could argue that the way race is expressed throughout these books are quite outdated and racist.

For example, it is widely accepted that a character like Atticus Finch is who we should all be looking up to when it comes to advocating for those who are oppressed. But one could also argue that due to the helplessness and lack of agency from any black characters in the book, Finch is basically the poster-child for the white savior complex.

If we look at how the n-word is used over two hundred times in Huckleberry Finn, one could argue that its usage provides an accurate depiction of a time period. But one could also say that it normalizes the usage of the word and potentially causes distress for students of color in the classroom. So what do students and teachers think about the inclusion of these books?

“I personally think that we should keep reading these books because they do shed light on the stems of where racism comes from,” answered Oliver Kane, a junior at Pentucket. “Every single student should have to learn and understand what those people have gone through throughout history. They are also just really good literature and very interesting books.”

“I think it is important that we continue to read these books because they provide an accurate depiction of certain time periods. It’s wrong to sugarcoat the way that people thought back then,” answered Zach Rosario, a junior.

“I’m torn on this one,” said Megan Friermuth, another junior. “It’s tough because addressing the racist undertones in the books can be a teaching moment of how normalized the racism really was, but these issues can be a bit harder to grasp for some students when they are reading books like these.”

She then added, “If we are looking for a more accurate depiction of racism, we should go to a better source than just a white perspective.”

Megan raises an incredibly valid point.

Diverse Sources and Authors

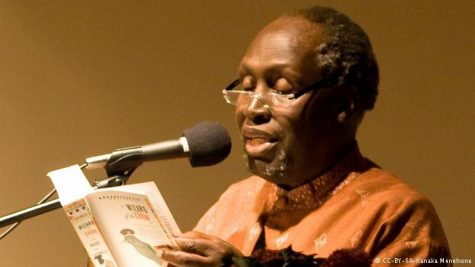

If we look at the major books being questioned, it is clear that almost all of them have been written by white men. This undeniably underlines a much larger problem in the way that we learn about race in school. In my interview with Mr. Casey, he introduced to me a Kenyan novelist by the name of Ngugi Wa Thiong’o. Thiong’o’s writings about the injustices of dictatorial government are incredibly powerful and provide a needed conversation for students. Some of his most famous works include Petals of Blood, A Grain of Wheat, and Weep Not, Child.

So what makes an author like Thiong’o have a more valid perspective than a Mark Twain or John Steinbeck? Including the writings of black authors into our schools’ curriculum adds to the conversation in a way that white authors simply cannot, just based on their own personal experiences. This inclusion is especially important for Pentucket because of the lack of diversity inside of our school walls and in our area. So what do teachers and students think about including a wider range of diverse authors?

When asked this question, English teacher Mrs. Kobuskie responded, “What I have found is that in some of my freshman and sophomore classes, looking at shorter pieces with varying perspectives works well. Reading and discussing these pieces, often in conjunction with other books, helps students make connections that may be difficult for them otherwise.”

I think that incorporating smaller texts written by black authors is a great way to incorporate varying perspectives, and I applaud any teacher who is taking these necessary steps to provide a balanced education. However, I had to ask myself an important question: is making teachers condense the black experience to short stories and excerpts really fair when our school is dedicating massive amounts of time and money to the writings of white authors?

“I think if we are going to be reading anything that has any correlation to race or racial issues, then the most valid perspective we could possibly get is somebody who has actually been oppressed because of their race. I feel like it just makes the experience so much more genuine,” answered Gwen Faino, another junior at Pentucket.

Throughout my interviews, it became clear that the student body is looking for more diversity in perspectives than what is currently being offered in the Pentucket English department. Limiting educational discussions about race to mostly white authors is not beneficial for anybody. If we really want to receive a balanced education about race, we should be spending the same amount of time reading from black authors as we do from white authors, if not more.

How Young is Too Young to Learn About These Topics?

If we can agree that teaching about race and racism is important, then how young is too young for students to be taught about race in class through literature? And to what intensity should young kids be reading about it?

I thought a great person to ask would be Mrs. Erhardt, an ELA teacher at the Page School.

“It’s important for students at a young age to begin to understand the roots of where social injustices began,” she answered. “As long as it’s taught appropriately, I believe it’s important.”

This brought me to my next question: how direct should our conversations about race be to impressionable young students? More specifically, should elementary students be reading books that contain the n-word in school?

Speaking from my own experience, I can recall a time in elementary school when a classmate of mine was told to read aloud a passage from a book that contained the n-word. This was followed by a dialogue from our teacher about how the word is okay to say when we are discussing it for educational purposes. But is including this word inside of books read by elementary school students a dangerous idea?

“I think kids shouldn’t be reading that word in elementary school,” answered Scott Redgate, a Pentucket alumni who graduated last year. “I know if I had to read that word in 4th or 5th grade, I wouldn’t have taken it seriously enough.”

Other students believe that teaching the word to young students can provide a necessary conversation about race.

“I believe that if a black child can be called the n-word, then a white child can learn the historical weight of what that word means. I wish that I had a better understanding for when I heard that word as a kid,” said Friermuth.

While the responses to this question were very mixed, I think that most of us can agree that the topic of race should be handled very delicately in elementary school classrooms.

What Actions Can We Take Moving Forward?

The movement to teach anti-racism in high schools nationwide is an incredibly important agenda and conversation. But the sad reality behind the negligence to teaching anti-racism in school is that a wide percentage of educators are not anti-racist themselves. Being anti-racist is more than possessing the simple attribute of not being racist. To be actively anti-racist is to take extra steps and dedicate time to promoting racial tolerance and opposing racist ideology. Anti-racism is incredibly important in education, but I don’t believe that this concept has been spread far enough across American schools. I think that until more diverse literature is encouraged in our educational system, we should all take it upon ourselves to become educated on racial issues.

I believe that as a collective, we should all be taking greater strides to educate ourselves. But, most importantly, I think we should all be doing a lot more listening. I’m going to include a short list at the end of this article of great black authors and books that we can all learn from and enjoy. I encourage everybody reading this to broaden their horizons and take the time to listen and understand the depths of the experiences of others.

W.E.B Dubois – The Souls of Black Folk. Dusk of Dawn. The Talented Tenth.

Angela Davis – Women, Race, and Class. Are Prisons Obsolete? Women, Culture, and Politics.

Angie Thomas – The Hate U Give. On the Come Up. Concrete Rose.

Ed Gordon – Conversations in Black : On Power, Politics, and Leadership.

Langston Hughes – The Weary Blues. The Big Sea.

Sojourner Truth – Ain’t I A Woman. The Book of Life.

Imbolo Mbue – Behold The Dreamers

E. Patrick Johnson – Black. Queer. Southern. Women. An Oral History

Ngugi Wa Thiong’o – A Grain of Wheat. Weep Not, Child. Decolonising The Mind. Petals of Blood.

Toni Morrison – Beloved. The Bluest Eye. Song of Solomon.

Maya Angelou – I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings. The Heart Of A Woman. And Still I Rise.

Kiley Reid – Such a Fun Age.

James Baldwin – The Fire Next Time. Go Tell It On The Mountain. Giovanni’s Room.

Martin Luther King – Why We Can’t Wait. The Measure Of A Man.

Candice Carty Williams – Queenie.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – We Should All Be Feminists.

Ibram X Kendi – How To Be an Antiracist.

Thank you for reading.

Cynthia Cromwell • Mar 12, 2021 at 12:32 pm

This year I added August Wilson’s play Fences to my 11th grade class. We read the play aloud. Since it includes multiple uses of the “n” word, students elected to substitute other words for the offensive phrase. The play, written by an African American, uses the word between the all African American characters. While the play’s use of the phrase is intense, the larger context of the play addresses the plight of African Americans in the 1950s, in particular, Black athletes. Excellent text.

Ms. Ducolon • Mar 11, 2021 at 12:26 pm

Just wanted to add some texts that we are already teaching:

Dr. Ruland teaches Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” to his AP Language class. Next year, the nonfiction text, “The Other Wes Moore” is being moved to sophomore year. Ms. Fichera does literary circles with books on racial identity in American Lit, and Ms. Treado covers numerous cultural identities in World Literature. In Graphic Novel and freshman English, we teach “American Born Chinese.”