A Month to Remember

November 1, 2021

Every October, LGBTQ people celebrate the rich history of protest, rebellion, and joy the community boasts.

With how little LGBTQ history is discussed in the media and the classroom, this month is essential to honor the people who risked their safety and their lives to get the community to where it is today.

Below is a list of ten instances of rebellion and tenacity from the LGBTQ community, ranging from the 1959 Cooper’s Donut riots to the first Dyke March in 1993.

Cooper’s Donuts Riots (1959)

It was a hot May in Los Angelos, Cooper’s Donuts was thriving, and the city was about to taste sickly sweet queer rage. The titular restrant was considered a safe haven for trans people- often banned from gay bars as a result of the police presence they drew. Indeed, violent police raids on Cooper’s Donuts following allegations of cross dressing, but the trans community refused to give up their foothold.

As the raids continued, the tolerance exhibited by the restaurant’s patrons began to fold to indignation and rage. One warm night, police raided the bar without notice- a routine event -and attempted to arrest two drag queens, two male sex workers, and a gay man. However, this hot night was different: the air crackled with something other than heat, and this rais would not end like the others.

The police rounded up their prisoners, herding all five into the backseat of one cruiser. An unidentified arrestee began to resist, complaining of lack of space- and with that, the May twilight exploded.

That shout set the city alaze; trans men, women, drag queens, and sex workers poured out of the restruant and fougt the police with coffee, chairs, donuts, and fierce resolution. Police forces retreated, abandoning their detainees, and queer Los Angelos rejoyed. John Rechy, witness to the events, stated that “…the street was bustling with disobedience. Gay people danced around the cars.”

A few hours later, police enforcements wrestled back control of Main Street. The riot died out, and was largely forgotten in history: just a spark in an otherwise grey time period for queer folk, a spark that never quite caught.

However, this riot proves just how long queer resistence has brewed in America, proves that the community has always been fighting back. The Cooper’s Donut Riot was the first documented queer riot in America, one of the first steps towards Stonewall, and therefore presevring it in queer history is essential.

First Gay Rights Demonstration (1964

(left to right) Renee Cafiero (Homosexuals Died For U.S Too), Jefferson Poland (Army Invades Sexual Privacy), and Jack Diether (Love and Let Love) at the U.S National Army picket. Source: Randy Wicker.

The first organized protest for LGBTQ rights occured September 19, 1964, directly in front of the US Army Building in New York City.

Led by Randy Wicker of the Homosexual Leauge of New York, it protested the military’s horrific treatment of gay soilders. This ranged from dishonorable discharges on account of homosexulaity, to sending potential employers records of soldiers’ sexuality in a disgusting violation of privacy.

The HLNY was joined by the New York City Leauge for Sexual Freedom, a mostly straight group whose support marked one of the first public unions between gay and straight activists.

The picket was ignored by the media, and as a result was unsuccessful in repealing the militaries homophobic practices. However, it remains the first documented instance of queer people banding together intentionally, planning a peaceful pritest, and executing it. The spirit and bravery of the protestors, especially against a foe as gargantuan as the U.S military, should never be forgotten.

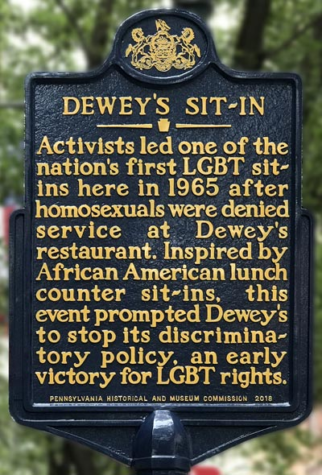

Dewy’s Sit Ins (1965)

In 1965, Dewy’s restaurant in Philidelphia was a booming spot for LGBTQ teens. However, one night a group of queer teens became disruptive- and management lunged at the opportunity to use the actions of a small group to justify their homophobia and bigotry.

In the days following the incident with the teenagers, management swifty declared a new rule: anyone who appeared homosexual or transgender could be denied service. Employees did not hesitate to enforce this ruling, turning what had been a safe space for queer youth into one of humiliation and injustice.

In wake of this injustice, Philiedehpia’s queer youth banded together. They took inspiration from the sit-ins Black American’s orchestrated during the Civil Rights movement, and began planning their own resistance.

On April 25, 1965, three teenagers led a group one hundred and fifty strong into Dewy’s restaurant. They refused to leave until they were served, and the three teenagers ended up being arrested. However, the Janus society, who had attended in support, managed to distribute over 1,500 pamphlets to Dewy’s patrons in the following days.

On May 2nd another sit-in took place, and after this instance the ruling against LGBTQ patrons at Dewy’s was reversed. Queer youth could once again enjoy their restruant without being harassed and degraded by staff- change had come, and they brought it themselves. As a result of their perseverance, the Dewy’s sit-in is the first LGBTQ protest in America that ended in a definitive victory.

New York ‘Sip In’ (1966)

‘Sip In’ protestors being denied service at Julius’.

On April 21, 1966, members of the gay rights group Mattachine Society took a stand against the New York State Liquor Authority’s regulation that alcohol could not be served to homosexuals. This law was enachted because queer people were too considered too ‘disorderly’ to be trusted with liquor- a law both ridiculose and cruel as gay bars were one of the few places LGBTQ people could gather freely.

The Mattachine Society entered the Julius Bar, took their seats, delcared they were gay, and waited to be served. Upon being denied service, they promptly took their case to court. From there, the judge declared that it was unconstitutional to refuse a person service on account of their sexuality.

As a result of their bravery and commitment to justice, the Mattachine Society’s legal battle against New York is remembered as the first time LGBTQ people won a case for their rights in a court of law.

Compton Cafeteria Riots (1966)

The Compton Cafeteria riot occurred in August 1966, three years prior to the Stonewall rebellion.

Compton Cafeteria, located in San Francisco, was a favorite spot for trans women. As a result, it was a hotspot for police raids and harassment. Trans women were often arrested for the crime of “female impersonation”- sometimes, just for having buttons on the wrong side of their shirt.

The Vanguard, one of the original gay-youth orginizations, also frequented the restraunt. They were banned by the owners in July, and protested both this injustice and the persecution of trans women on the nineteenth. While unsuccessful, it laid important groundwork for next month’s riot.

One night in August (the exact date has been lost) police arrived at the restaurant after reports of ‘rambunctious behavior,’ and attempted to arrest a trans woman. The woman responded by throwing coffee in the officer’s face, and the restaurant erupted into the first anti-police brutality protest in the defense of a trans woman.

Tables and sugar shakers were thrown as the fighting moved outside and the police called in reinforcements, attempting to make arrests. While the fighting eventually died down, the next day LGBTQ people were banned from Compton’s entierly, leading to a large protest outside the building that failed to yield strong results.

Although largely forgotten by history, this was the first protest in America that revolved entirely around the safety of a trans woman. Therefore, as the number of murdered trans women continues to rise, it is an event that everyone, both in the community and out, should keep close to their heart.

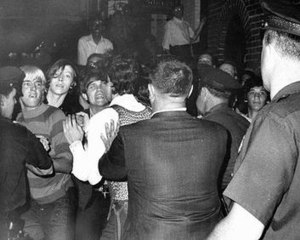

Stonewall Uprising (1969)

On June 28th, 1969, what many would consider the official start to the LGBTQ activism movement in America would officially ignite.

Police raided New York’s Stonewall Inn, arresting thirteen people. As people were being dragged away, a woman (rumored to be drag king Storme DeLaverie), called out “why don’t you guys do something?”

That shout called forth a revolution. For one moment, it was a lone spark in the night, and in the next- the world was on fire.

Inn patrons stormed into the streets, attacking the police with tables, chairs, and anything else they could reach. Parking meters were uprooted, miros were smashed, a Rockette-style kick line formed in front of the police. Offierc retreated inside a building, which was nearly torched. The police fought back with water hoses and batons. an uprising that lasted six days, with the number of participants ranging from the hundreds to the thousands.

Stonewall was home to Drag Queens who were thrown out of more legitimate gay bars, and to the hundreds of homeless LGBTQ teens on the streets of New York who couldn’t afford to find community anywhere else.

This barely-legal bar became home to New York’s outcasts, so when it was threatened and the tension finally broke, those who had been protected by it rushed to return the favor.

By the end of the night, the police left with none of those they attended to arrest, and a whole new wave of LGBTQ activism had been ignited.

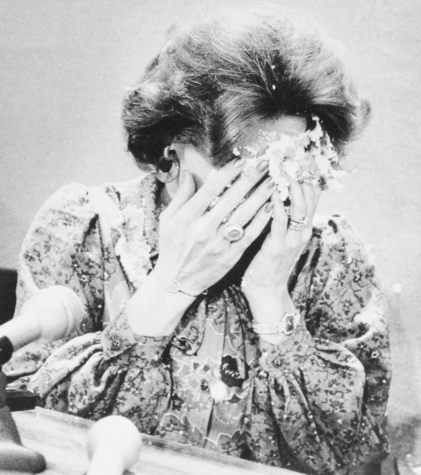

‘Zapping’ (1977)

Anti-lgbtq rights activist Anita Brant after being hit in the face with a pie by infamous ‘zapper’ Tom Higgins.

In the 1970’s, one of the more popular methods for ‘curing’ gay men of their homosexuality was through electroshock therapy.

In response to this, as well as the new emphasis on aggressive activism that began after Stonewall, came ‘zapping.

A ‘zap’ was a fast, loud alternative to more peaceful protesting, which managed to combine practical jokes and action into one. The idea was coined by the Gay Activists Alliance’s Marty Robinson,- later nicknamed ‘Mr. Zap.’

Charles Silverstien zapped a conference on electroshock therapy as conversion therapy. He entered the conference, announced he would take over, and then did so with such effectiveness that he was invited to give a proper presentation of his own.

The GAA, alongside with the Daughters of Bilitis (a lesbian activism group), then zapped a New York company known as Fidelifacts.

Their president has stated that his policy for idenfiying gay employees (and subsequently harassing them) was: “if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, associates only with ducks and quacks like a duck, he is probably a duck.” The GAA, Daughters of Bilitis, and other protestors lined up in the streets in front of the offices. Many squeaky rubber sucks, and one even dressed in a full duck costume, in order to protest this policy. While painted as ‘silly’ by the media, this protest brought much support to their cause

Another famous zap occured in December 1973. Protestor Mark Segal interrupted a CBS news segment that was airing for sixty million people, holding a sign that protested the limited way CBS covered LGBTQ news. The zap was successful, and CBS began covering LGBTQ news soon after.

Finally, in 1977 famous singer and anti-gay rights activist Anita Bryant was giving a press conference. Suddenly, Tom Higgins rushed forward and hit her in the face with a strawberry pie. This both damaged her credibility while giving the LGBTQ community a much-needed victory against her hate speech.

While Anita Bryant kneeled in prayer for Higgins to be saved from his homosexuality, the later smiled, clearly satisfied.

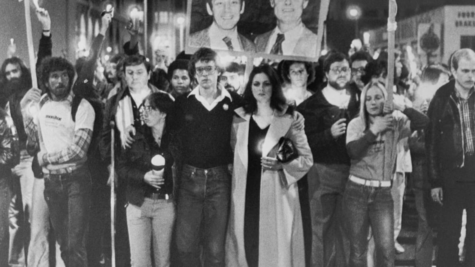

White Night Riots (1979)

On May 29, 1979, former police officer Daniel White was convinted of the manslaughter after he assassinted Harvy Milk and Mayor Monscoe- the former of which was the first openly gay elected official in the United States.

White was origially charged with murder, but got a lesser sentencing after pleading that he was not in a sound mental state at the time of the murders. Him eating an excessive amount of junk food was accepted as evidence for this. He was sentenced to seven years and eight months in prison.

The verdict enraged the LGBTQ community of San Fransico. A man who had been a beacon of hope for queer people being accepted in society, had been slaughtered. Now, the justice system was bending over backwards to give the murderer a light sentence, while Milk had been harassed every day he was in office and received no support.

Cleve Jones led a 5,000 person strong march, which clashed dramatically with police. Officers taped over their badges to prevent identification, then brutally attacked the protestors. White was an ex-cop, and even as a murderer he still received their support and sympathy.

The riots calmed, but the police did not. They stayed on the streets, attacking anyone they found- protesters or otherwise. None were punished.

20,000 people attended a peaceful protest in honor of Milk the next day. On October 14 of the same year, protestors marched on Washington for gay rights. This march was something Milk intended to help organize. Many people carried signs with his face and name. While White’s verdict was never changed, the San Francisco community was still able to honor Milk and everything he accomplished, carrying his legacy into the future.

Die Ins (1992)

Wayne Turner with his dead partner, Steve Michael, during an AIDS protest in front of the White House on July 4th, 1998.

In the late 1980’s, the AIDS crisis was rapidly growing with no acknowledgement from the President and no hope for a vaccine.

As their cries for help continued to fall on deaf ears and the death roll grew steadily, the LGBTQ community began protesting to bring media attention to this ‘silent pandemic.’

At first, the driving force behind these protests was pure rage. According to David France, protesters “would storm people’s offices with fake blood and cover people’s computers with [it]…they locked themselves to politicians’ desks. At one point, they barged into a meeting of a pharmaceutical company and turned over the shrimp cocktail tables.”

However, the AIDS activist group ACT UP slowly grew and organized. With this new sense of structure, the actions taken by protestors became more calculated and direct.

One such method they used was “die ins.” A particularly effective ‘die in’ took place on April 11, 1988, in front of the FDA headquarters. A massive group of protestors feigned death on their steps. They wore signs such as “DEAD FROM LACK OF DRUGS” and “KILLED BY THE SYSTEM.” Spurred into action by this protest, the FDA approved access for a drug to help treat AIDS less than a year later.

Another protest, taking place on October 11, 1992, was nicknamed “Ashes Action.”

Protestors gathered in Washington DC, and in one of the most sombering, bone chilling acts of the time, sprinkled the ash of loved ones who had died on the lawn of the white house, bringing the pain Reagan had caused right to his doorstep. Some even brought corpses in open coffins to demonstrate their point.

As a direct result of these protests, the Regan administration finally acknowledged AIDS as a health crisis. Treatments that would have only been dreams otherwise were brought into fruition, and because of the bravery and determination of these activists, countless lives were saved.

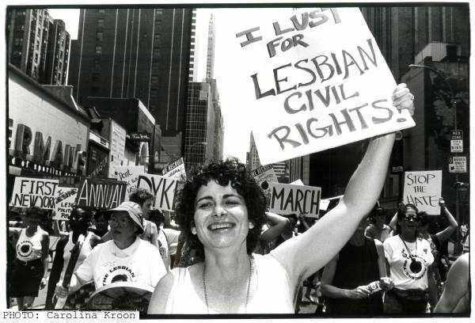

Dyke March (1993)

The first Dyke March took place in April, 1993, with marches popping up in LA and DC.

The New York Lesbian Avengers handed out over eight thousand flyers encouraging lesbians to join them in a march on Washington, and in the end over twenty thousand did.

In June, New York held their own Dyke March- without a permit. So many years later, it is still tradition to not acquire a permit for this march. This, in order to preserve the original sentiment of civil disobedience that the first protest held.

A manifesto encouraging organization amongst lesbians was distributed, and a banner was created on the spot to be carried at the front of the march. This was another symbol of the Dyke March that has withstood the test of time- the march is still led by a banner today.

At the second New York Dyke March, there were over twenty thousand attendees- enough that the parade had to be led by a group of drummers in order to stay organized. Today, the Dyke March is still led by drummers.

This first march was an incredibly important moment in LGBTQ history. So much of queer history is devoted to gay men, it is essential to honor and celebrate the lesbians who also fought for their rights. Lesbian activists have always been an intergal part of the LGBTQ rights movement, and forgetting them is detrimental to preserving queer history. These woman, and their fight to make sure homosexual women were not left behind in the fight for marriage and sexual equality, must be given the honor and respect they deserve.

In Memory.

It is essential that these events are remembered and the people involved honored, by both people outside and in the community. As a result of police brutality and the AIDS crisis, almost an entire generation of LGBTQ people are either afraid to come out of the closet, or buried six feet under. They helped create history, but are unable to share their accomplishments.

Furthermore, LGBTQ education is scarely taught in schools- and when it is, it only glosses over the legalization of gay marriage. No mention of the protests, the riots, the people who laid down their lives so LGBTQ people could enjoy the privleges they now have.

That is why October is so important. It reminds people to seek out LGBTQ history that would otherwise be lost, and gives a chance for activists forgotten by history to be given the recognition, respect, and honor that they deserve. In these last remaining days of October, make a point to research the history of the LGBTQ comminity, both in America and beyond its borders. Success is dependent on knowing one’s history. If we lose sight of our past, of what worked, what didn’t, and how progress was made, the forward progress the LGBTQ community has been making will slowly grind to a halt.

That cannot be allowed to happen.