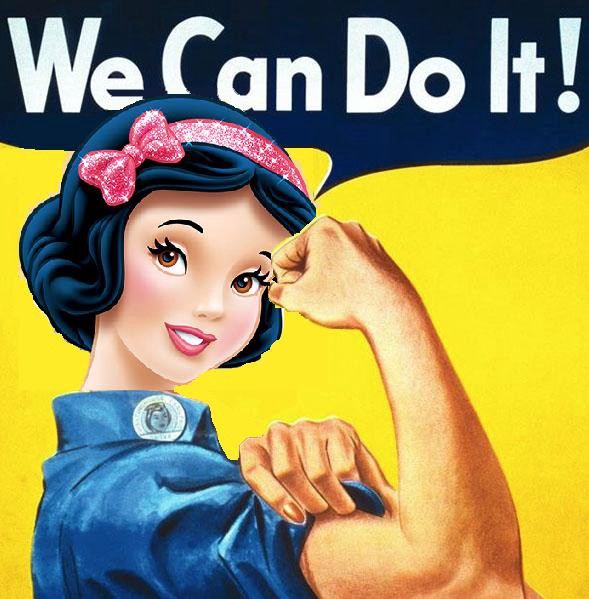

Girl Bosses Wear Dresses Too

Photo Source: CineNation

November 8, 2021

They’re doormats. They’re stereotypes. They’re damsels in distress. They’re bad role models for young girls.

Such is the mindset of a society becoming increasingly alienated from the Disney princesses of old.

The character lineup itself has undergone dramatic rebranding in recent years, with new princesses such as Elsa, Merida, and Raya introducing a new, trail-blazing type of princess: sword-wielding warrior women who wear pants and don’t need a man.

But it remains to be seen whether or not these princesses are truly so much superior to their older counterparts as modern audiences believe them to be.

With the introduction of these updated heroines, the vintage princesses have fallen increasingly from societal grace, being dubbed out-dated relics of a bygone past that serve only to promote dependency on men, passivity, and helplessness–criticisms that essentially condemn the conventional femininity that these princesses represent as itself “unfeminist.”

Actresses Kristen Bell and Keira Knightley have even said that they do not allow their children to watch the older Disney princess movies due to beliefs of their negative portrayals of women, or as Knightley says, Cinderella just “waits around for a rich guy to rescue her.”

Similarly, actress and prominent feminist Emma Watson turned down the role of Cinderella in the 2015 live-action remake because “she didn’t believe that particular princess was enough of a role model.”

These criticisms, however, in of themselves contradict the very concept of feminism. As defined by Emma Watson (contradicting her own criticisms of Cinderella), feminism is “about giving women choice. Feminism is not a stick with which to beat other women with. It’s about freedom, it’s about liberation, it’s about equality.”

Is there not, therefore, some policing of the female identity in society effectively telling young girls which dreams they should or should not have and what ‘type’ of girl they should or should not be (‘girly’ vs ‘tomboy,’ single vs romantically-involved, gentle and optimistic vs warrior-like)?

For this is the mindset of the criticisms of the classic Disney princesses. The increased ‘masculinization’ of the princesses–having more of them wear pants, be interested in archery or sword-fighting, and lack romantic partners–effectively perpetuates the societal mindset to young girls that masculinity is inherently superior to femininity.

Conventional ‘girliness’ is being scrutinized in favor of promoting modern and stereotypically ‘tomboyish’ female heroes such as Captain Marvel, Katniss Everdeen, Black Widow, or Wonder Woman–all ‘badass’ superheroes, warriors, and defiers of all things ‘girly.’

While the representation of such women in the media is of course positive and necessary for young girls to see, their existence does not, however, make the ‘traditional’ femininity represented by the older princesses a sign of comparative weakness. Rather, this one-sided representation of women erases an entire aspect of the female identity, effectively shoving the concept of womanhood into a strict box of acceptable vs unacceptable expressions.

When getting down to the basics, the classic Disney princesses do still provide timeless messages of kindness, compassion, optimism, and perseverance, all of which are not in any way negative traits.

These traits, each one of them connected to the traditional caricature of the female, are the predominant characteristics associated with Cinderella, Snow White, and Aurora.Society’s condemnation of their characters as “weak” and “passive” therefore only serves to draw a harmful correlation, rather than a progressive one, between kindness and weakness. But when one actually examines the characters closely, the opposite is the case.

Though not charging into battle like Mulan, or shooting arrows off the back of a horse like Merida, these princesses display a gentler sort of fortitude in their own rights.

Although on the surface Knightley’s claims about Cinderella’s passivity may seem convincing, they offer only a surface-level view of her story, as the criticism not only ignores the nuances of Cinderella’s situation as an abuse victim, but also erases the empowering strength she does possess.

Despite living most of her life in an abusive and loveless family, Cinderella displays immeasurable strength through her ability to maintain a hopeful outlook on life that “no matter how your heart is grieving, if you keep on believing, the dreams that you wish will come true.”

Snow White, too, despite having almost been murdered at the request of her own step mother, and then facing the reality that she has no home, quickly collects herself, telling the forest animals, “I’m so ashamed of the fuss I’ve made” and steeling herself that “with a smile and a song” she can turn her situation around and find a solution. Still, these princess’ quietly-empowered personas are wrongfully labelled as shortcomings.

And of course, there is the ever-present idea that for a woman to be independent, she must be physically alone.

Another chief criticism of the older Disney princesses is that their stories largely center around romance, making the princesses all the more weak and dependent for it. When the trailer for the 2020 live-action Mulan was released and it was revealed that Mulan’s love interest was being written out of the movie, many responded to the change with support, believing that “Mulan doesn’t need a man” and agreeing with the film’s producer, Jason Reed, who said that given “the time of the #MeToo movement,” he “didn’t think [the relationship] was appropriate.”

As evidenced here, the very concept of a female heroine being romantically involved is viewed as automatically erasing her agency, even though Mulan’s romantic subplot with Li Shang is just that: a subplot that takes up hardly any screen-time in the movie, as the pair only formally get together in the last scene.

Rather, the association between female love and weakness exhibits another problem with the Disney princess criticism, in that it encourages emotional repression in women.

When Frozen 2 was released in 2019, the film was widely praised for its portrayal of Kristoff, particularly his emotional power ballad “Lost in the Woods” where he pours out his love for Anna, singing “who am I, if I’m not your guy? Where am I, if we’re not together forever?” This exhibition of emotional vulnerability was heralded as refreshing and necessary, as Frozen actress Kristen Bell described in a Jimmy Fallon interview to promote the film. “Little boys don’t often see representation of other boys having really big loving feelings,” said Bell. “There’s a line in the song that says, ‘You feel your feelings and your feelings are real.’”

Yet if a Disney princess had sung the same lovey-dovey lyrics as Kristoff (as they historically have in ballads such as ‘Someday My Prince Will Come’ or ‘Once Upon a Dream’), she would be automatically deemed dependent and weak. This criticism effectively evidences and exacerbates the clear double standard between the ways male and female characters are allowed to express emotion in the media, seen through the fact that the bulk of female representation that is deemed “empowering” today consists of stoic action heroes. Again, this only serves to bottle up the boundaries of the female identity by dictating what a woman should or should not be.

The representation of female heroines who are superheroes, soldiers, leaders, and ‘tomboys’ is necessary in conveying to young girls the limitless opportunities they have to soar. But equally so is the portrayal of female characters that resonate with the more stereotypically ‘girly’ sensibility.

Desiring to find true love in life is just as valid as wishing to remain self-partnered, and exhibiting more traditionally ‘girly’ traits does not automatically disqualify a woman as weak or complacent. It is the favoring of one avenue over the other that in truth serves to constrain the dreams of young girls rather than encourage them, and thus the importance lies in striking a balance between the types of women the media portrays.

Femininity takes shape in all forms and sizes, and neither one is inherently superior to the other as the modern Disney princess mindset suggests. Dictating what kinds of princesses we see in the media and deeming certain ones ‘bad role models’ only further serves to suppress female identity and in turn violate the freedoms of feminism such criticisms claim to protect. After all, queens wear crowns for a reason.

Sources

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/lindamaleh/2020/02/28/disney-blames-metoo-for-li-shangs-absence-from-mulan-in-new-controversy/?sh=69f92ee85965

- https://www.today.com/parents/kristen-bell-keira-knightly-think-some-disney-stories-send-wrong-t140064

- https://www.elle.com/uk/life-and-culture/culture/news/a33458/emma-watson-turned-down-cinderella-before-belle/#:~:text=Watson%20has%20revealed%20she%20was,enough%20of%20a%20role%20model.

- https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/television/8543447/frozen-kristen-bell-jimmy-fallon-history-disney-songs