Should Americans be Learning Foreign Languages?

October 31, 2021

There’s an old joke that goes along the lines of:

What do you call someone who speaks two languages?

A bilingual.

Someone who speaks three?

A trilingual.

And someone who speaks one language?

An American.

Even though it’s corny and often told sarcastically, the joke has an unfortunate amount of truth to it.

The United States’ poor multilingual track record

American language proficiency is far from exemplary. On a global scale, it’s pretty dismal. We do not compete with the rest of the world when it comes to bilingual ability.

According to MVOrganizing, only 20.55% of Americans can communicate in a language beyond English, compared to 60% of the global population. With an almost 40% difference, there would ideally be an initiative to close the gap. Unfortunately, there is not much hope for improvement.

American students begin learning languages late and stop early. Language instruction normally begins in middle or high school and drops off in college. Elsewhere, languages begin to be taught in early elementary school and continue to later in life more often.

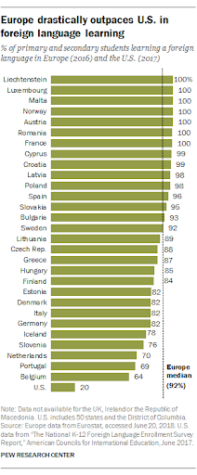

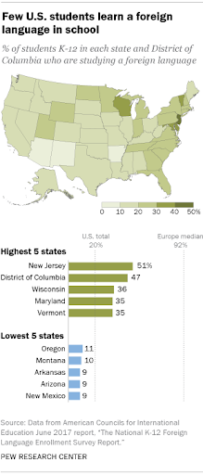

From grades K-12, the gap between the United States and the rest of the world is stark. Europe’s average of primary to secondary students learning a foreign language is 92%, including countries such as Germany (82%), Spain (96%), Poland (98%), and France (100%), according to Pew Research. The U.S., from the same survey, proved to only be teaching 20% of its K-12 students a second language.

The country stacks up just as poorly with its other English-speaking neighbor. Canada teaches its students French or English, depending on which is the students’ primary language. Both are the national languages of Canada, making it an officially bilingual country. From Canadian encyclopedia

In order to be so behind in language education, there must be a valid reason.

Why are we not learning other languages?

The disparity, largely, is simply caused by a disinterest in the education of foreign languages. As a country, we have not incorporated language learning as part of our identity. The U.S. is considered to be a country made up of many cultures by immigration, yet we do not teach ourselves the languages spoken throughout the rest of the world.

This disinterest may be caused by the common notion that Americans don’t learn languages, historically. The U.S. has always been an English-speaking country over the course of its history.

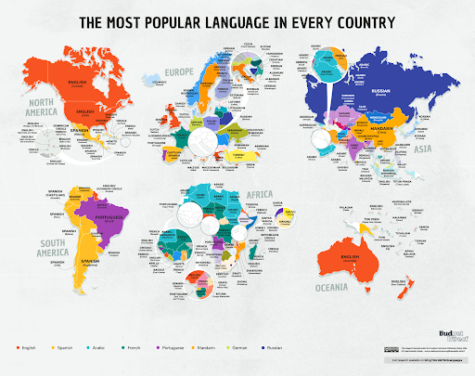

It could also come from the prevalence of English domestically and internationally. The idea is, if everyone else speaks English, why does the U.S. have to learn foreign languages? Americans tend to see English as the global language, but according to the World Economic Forum, only 1.5 billion people speak English worldwide. Not to mention, of this population, less than 400 million speak it as their native language.

Although English may be the most commonly spoken language in the world, it is not at all a universal and always effective way to communicate. By learning other languages, one can open their horizons to the remaining 6.5 billion non-English speakers in the world.

Importance of multilingualism

Multilingualism, or knowing more than one language, has a wide array of benefits.

Simply being able to communicate with more people is the main benefit of learning other languages. The bottom line is- learning another language increases the number of people you can communicate with, whether it is a major world language or a minor dialect. It opens doors to more conversations, insights, and opportunities.

Languages are also useful in the job market. Being able to speak other languages, especially more than one secondary language, can increase your job prospects greatly.

At a time where employers are searching for talented people, knowing other languages opens up more career options. And, according to The Atlantic, U.S. companies are at such a loss for bilingual workers that they may need to start importing people who can speak the languages they need to communicate in.

Learning a language can also improve a person’s health. Language learning can double the chances of cognitive recovery for people who suffer from a stroke, per the BBC.

Additionally, a study presented by York University in Toronto from the same article stated that bilingualism has an effect on Alzheimer’s disease. An examined group of bilinguals proved to have a delay of five years in the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms to a group of monolinguals. Although it’s not a cure for the disease, knowing other languages can push the impact of Alzheimer’s symptoms by years.

Beyond benefitting the individual, multilingual citizens can benefit a society at large. Varied language skills elevate a country and society on many levels.

Politically, ambassadors and foreign ministers may interact more effectively with other countries and build better relationships internationally. Multilingualism also allows a country to better understand and keep track of foreign affairs.

Economically, a society that can do business on more levels is a successful society. An understanding of languages and cultures allows business relationships to flourish in foreign countries. In these countries, U.S. businesses can reach new customers and new markets.

And finally, a society that understands and respects other languages and cultures will be more welcome internationally. The U.S. has a not entirely false reputation for being incognizant of foreign cultures, which could be improved by a better understanding of the way the world speaks.

How to make a change

Fortunately, the lack of language education isn’t a problem with no solution. In fact, there are many ways to improve the state of language learning in the United States. All improvement, however, must begin with a desire for change. The U.S. must decide that a change is important before any change can be made.

Once a shift in attitude occurs, voters and lawmakers may enable emphasis and action towards learning languages in the U.S. Programs for increased learning for ages K-8 may be where the most important change can occur, since younger minds are best at picking up languages.

It’s important to remember that no language is useless. Learning any language will bring about the mind sharpening and health benefits that come with bilingualism. Even languages with no active speakers like Latin may not be effective in communication, but they will grant the same cognitive advantages. The only measurable difference in different languages’ values is in their prevalence. It may be a better idea to teach Spanish or French in schools than a language spoken by only a few thousand worldwide.

If an effort is to be made in boosting language education, more questions may open up. Just how young do we start at teaching languages? Do we teach the same languages in all schools across the country? What techniques will be used to facilitate multilingualism? What languages are the most important to be learning in the first place?

All these questions and more will inevitably be asked if a decision is made to bring on a change. If there is an upside to the current situation, however, any improvement is a necessary one.

Pentucket Educators’ Thoughts

To get their opinions, I talked to two Pentucket educators, Señorita Cavallaro and Frau Hackett.

Cavallaro, a Spanish teacher, spoke both of her own experiences and what she has seen in her teaching career.

Having family in Italy, Cavallaro spoke about how students there begin learning English in kindergarten and pick up another around the start of middle school. By the time students get to high school, they have learned more than two languages.

Coming from a bilingual family, Cavallaro has seen firsthand the benefits of learning languages. She talked about how her brother was offered a job by a reputable company in great part for his fluency in Spanish. During an interview process, one of the employers told Cavallaro’s brother that he was being hired even though there was a stack of applications from people more qualified than him. He was able to bypass all of the other applicants was because he knew Spanish, and the company needed someone bilingual.

Speaking on the general necessity of languages, Cavallaro talked about how the U.S. itself is a “melting pot” of cultures, and almost anyone in any field can find languages useful. Whether it’s medicine, law enforcement, business, education, or more, being bilingual assists in every field.

Cavallaro also spoke about how students of hers have gone on to move to, work in, and even marry in countries that they learned the language of. The amount of opportunities provided by learning languages is truly great.

German teacher Frau Hackett talked about many of the same ideas as Cavallaro, like the importance of languages. She also talked about where the condition of language education stands as of right now.

Recently, Massachusetts approved new curriculum standards for foreign languages. They now state that every student should learn a foreign language, classes should be spending 90%+ time in the target language, and use storytelling strategies. Although it may not be exactly on par with the rest of the world, it is a step in the right direction and the first such adjustment in 20 years, according to Hackett.

Another educational tip that Hackett shared was about the seal of biliteracy. I had never heard of it previously, and none of my classmates I asked had either. The seal is a mark that goes on a graduate’s diploma if they are able to pass the ELA MCAS and another test on their language taught in school. The seal has been given to six Pentucket students ever, who, Hackett says, all found ways to speak their languages outside of the classroom to boost proficiency.

And finally, Hackett and Cavallaro both talked about how interest will drive any change in the system of language education. With the new Massachusetts learning standards, it seems like at least some enthusiasm has gotten the ball rolling for improvement. Hopefully, more students, parents, educators, and administrators will agree that language learning is integral, and change will be made in the United States to reach higher standards of multilingualism.

Senorita • Nov 8, 2021 at 8:48 am

Thank you for writing this well researched and thought provoking article and shedding light on the gap of our national education system.

Bo Latham • Nov 2, 2021 at 2:44 pm

I feel like this is a very important topic that should be more prioritized in American education. The rarity of a dedicated language education has definitely led the US to lack in a wide range of languages. These limitations reflect poorly on our nation as a whole, as well as the awareness and care of our population. I’m glad to see someone address this national educational failure, and I hope it can be spread to people that have a more influential presence in the American Education system.